Crisis after Qaddafi: Analyzing the Factors and Possible Trajectories of the Libyan Civil War

Written by Patrick Iskandar

Introduction

In 2011, an unprecedented revolutionary tide swept through the Middle East and North Africa. Popular uprisings began in Tunisia, where President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali was driven out of power on January 14th. This inspired mass mobilization throughout the region, igniting civil disobedience and leading to the ousting of several leaders by the end of February. This wave of pro-democracy insurrection is known as the Arab Spring, and it had a considerably transformative (albeit heterogenous) effect on the region.

In Libya, the downfall of dictator Muammar Qaddafi – while monumental – was but a prelude to protracted conflict over control of the body politic. Libya’s experience in the aftermath of the Arab Spring has been a civil war wrought with factional infighting, teetering alliances, and proxy warfare by external actors. Still, its future is uncertain and global actors eagerly follow developments in a sovereign nation rich in both oil and geopolitical value. While the Libyan Civil War has complex roots, it has primarily been shaped by a historic lack of central authority and viable political institutions, continued foreign intervention, and to a lesser degree, societal cleavages among various groups throughout Libya.

This paper will begin with background information geared primarily towards contemporary developments in Libya before analyzing, in depth, each of the three aforementioned civil war factors. Finally, it will present multiple potential trajectories over the next three years, focusing on the most likely outcome. While the future is invariably unknown, it can be reasonably surveyed when complex vectors are taken into account, as follows.

Background

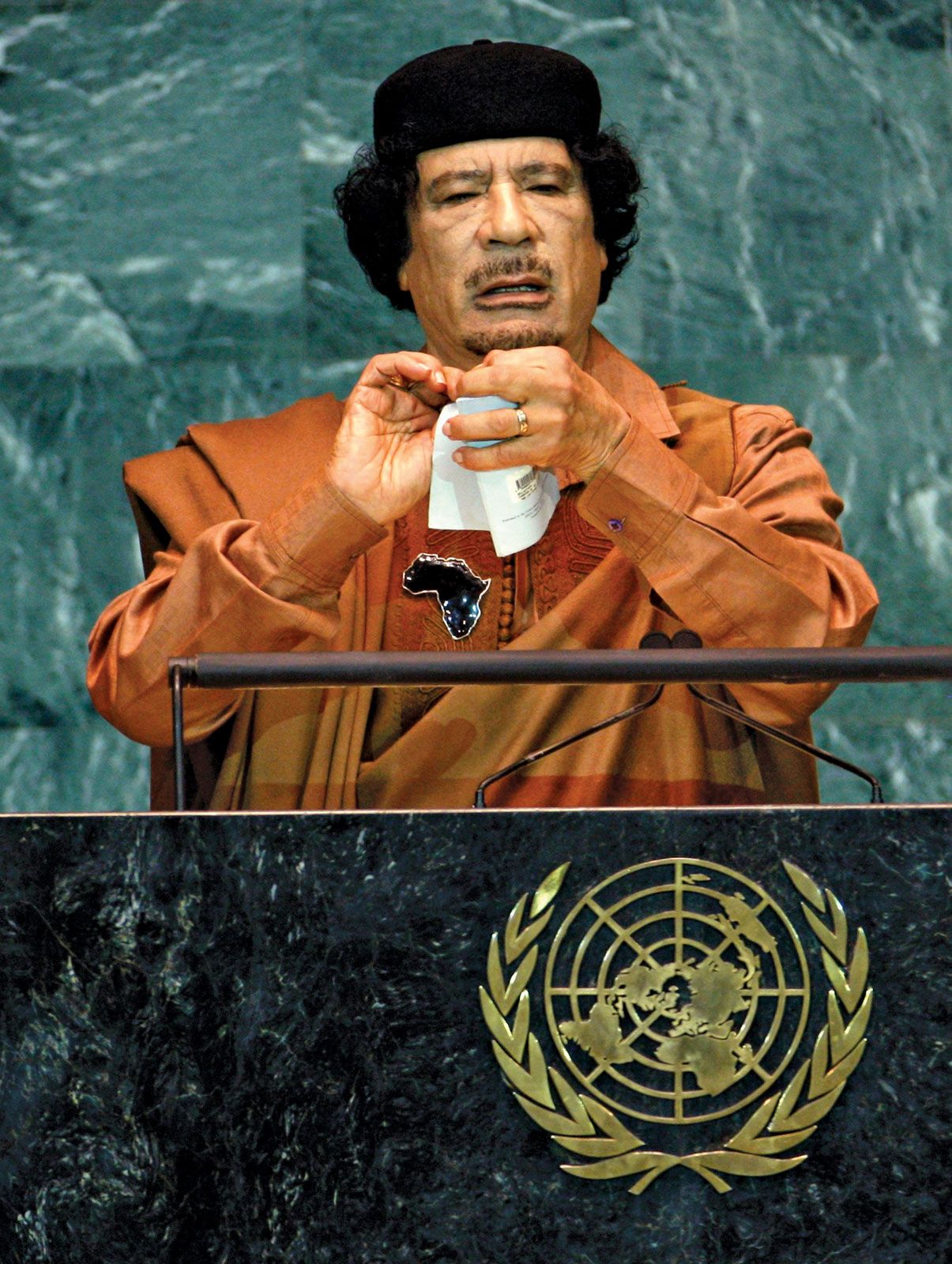

Colonel Muammar Qaddafi had almost omnipotent control over the character of Libyan governance for the 42 years after his successfully orchestrated coup against the presiding monarch. This monopoly went virtually unchallenged until mass demonstrations inundated the streets of Benghazi amidst the burgeoning Arab Spring and resulted in an armed struggle between rebels and pro-government forces. By February of 2011, a de facto government formed in opposition to Qaddafi known as the Transitional National Council (TNC), seated in Benghazi and declaring itself as Libya’s sole legitimate central authority. Led by Mustafa Abdul Jalil, former Minister of Justice under Qaddafi, the council began to garner international support and recognition, in contrast to Qaddafi, who continued to alienate himself from the international community in his relentless efforts to stamp out the rebellion.

Qaddafi was condemned by UN, the Arab League, the African Union, and others for his use of force against protestors and violations of human rights, and by March, a NATO-led coalition launched a military intervention. This coalition led mainly by the US, France, and the UK, supplied aid for rebels, conducted air strikes and implemented naval blockades, destroying a significant portion of the regime’s military capabilities. Rebels took the capital city of Tripoli in September, and on October 20th, rebels captured the city of Sirte and killed Qaddafi. Three days later, the TNC declared Libya to be liberated, and by the end of October, NATO operations in Libya had formally concluded.

Qaddafi’s death was followed by mass celebration and a temporary ceasefire, as the TNC began the process of transitioning Libya to democracy. While Qaddafi’s overthrow marked an important milestone in the country’s history, Libya’s struggle for democracy and stability was far from over. The TNC appointed an interim government to take power, as parliamentary and presidential elections were organized. Many remained skeptical of the TNC, as it was formed without national input and several of the council’s officials had ties to Qaddafi’s regime. Local militias across the country, but mainly in the West, refused to disarm, and these militias often clashed with one another.

Although marred by sporadic intimidation and violence, a parliamentary election in July of 2012 established a 200-member legislative assembly known as the General National Congress (GNC). In August of 2012, power was officially handed over from the TNC to the GNC in Libya’s first peaceful transition of power, but the GNC continued to face similar issues. The GNC was given 18 months to transition Libya to a democratic constitution, but tensions between local armed groups continued to intensify as the GNC failed to establish legitimacy in parts of the country. A month after the GNC was given power, Ansar al Sharia, an Islamist militia, stormed the US consulate in Benghazi, killing four Americans, including the US ambassador to Libya. Militias in the East seized oil terminals in order to gain leverage on the government, which relied almost entirely on oil exports for revenue. By the end of the 18-month mandate, the GNC remained deadlocked between Islamists and nationalists and had not made progress on creating a constitution. They attempted to extend their mandate, but the Libyan people protested, demanding elections and the government’s resignation.

As the GNC struggled to deal with the demands of militias, Khalifa Haftar, a former general under Qaddafi, set up a base in the east, consolidating power and calling upon Libyans to rise against the GNC, which he saw as dominated by Islamist groups. In May of 2014, Haftar launched Operation Dignity, a military campaign against Islamic and Jihadist militias, which had become quite powerful in Benghazi and the east. Elections took place in June in an effort to calm tensions, and a new parliament, the House of Representatives, was created to replace the GNC. Voter turnout was a mere 18% due to boycotts and security concerns, and Islamists performed poorly, left without sizeable representation in the new parliament. Many members of the GNC refused to accept the new House of Representatives, declaring the GNC to still be the legitimate parliament of Libya. In August, Operation Libya Dawn emerged in opposition to Haftar’s campaign against Islamists. Libya Dawn was a coalition of Islamist and Misrata militias, including the Libya Revolutionaries Operations Room (LROR) and Central Shield. The LROR itself is a coalition of Islamist militias, funded by the GNC in 2013 to provide security in Tripoli and Benghazi.

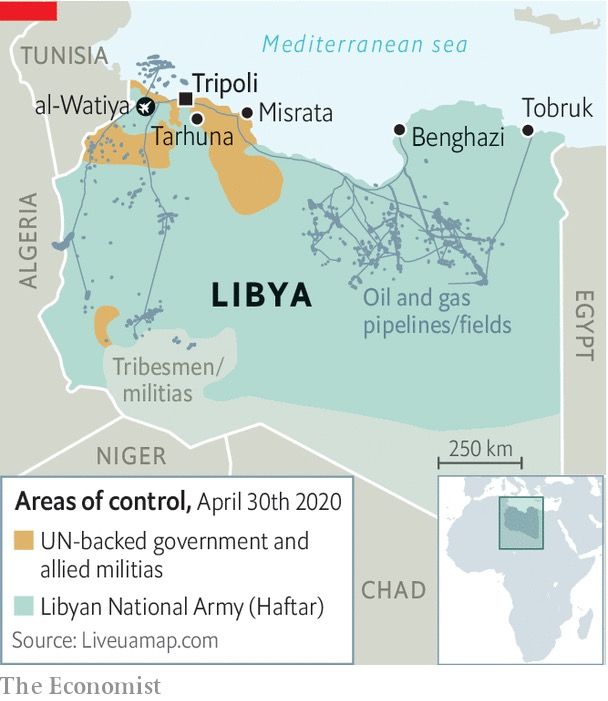

Libya Dawn forces entered Tripoli, taking control of large parts of it, restoring the GNC, and driving the House of Representatives east, out of Tripoli and into the city of Tobruk. In November, the Supreme Court ruled that the election of the House of Representatives was unconstitutional, bolstering the legitimacy of the GNC. However, Tobruk government officials did not accept this ruling, claiming that “Tripoli is hijacked” by Islamists, leaving Libya split between two rival governments. In response to this, the UN mediated discussions between the two parties, resulting in the Libyan Political Agreement, which established a Government of National Accord (GNA), led by Prime Minister Fayez al-Serraj. While the House of Representatives initially supported the GNA, they withdrew this support and refused to recognize the new government, instead aligning themselves with General Haftar in the east. Parts of the GNC backed the GNA, while others opposed it, but the GNC eventually dissolved, and the GNA had become the new internationally recognized government of Libya.

Since the emergence of the GNA, Libya has remained divided between rival governments, as instability and conflict continues to plague the country today. ISIS took advantage of the absence of a nationally recognized government, arriving in Libya in 2014 and taking control of the city of Sirte. Coalitions of militias, backed by US air support, were able to drive ISIS out of the area by 2016, but foreign powers have gotten involved, transforming the conflict into a proxy war and further destabilizing the country. This conflict has become protracted, with loose and constantly shifting coalitions on both sides, and this paper seeks to break down the political dynamics that have shaped this war.

Factors

- Lack of Central Authority

The absence of a legitimately perceived central government since Gaddafi’s ouster has arguably been the largest roadblock to stability and unity throughout Libya’s civil war. While attempts have been made to form parliaments and hold elections, the significant degree to which civil society is fragmented has hindered the ability of these councils to successfully court widespread recognition at the national level. The security and power vacuums resulting from such decentralization have incentivized factions and militias to consolidate power based on local or regional fissures. “The outcome has been an unstable stability, or a stable instability, in which each faction is in a position to limit the influence of others, but not to take control of Libya as a whole, and a functional impasse inhibits further progress on most issues of importance.”

Looking back on Libyan history, it is easy to understand why Libya has become so decentralized. Under Ottoman rule, Libya was divided into two parts, one containing Tripoli in the west and one containing Benghazi in the east. Under Italian colonization, political and economic institutions were not fostered on a national level, and by 1951, Libya emerged independent, but divided, with three different regions containing their own separate governments and institutions. Following independence, Libya came under the control of King Idris, and political parties and institutions were banned, with authority lying solely in the hands of the monarch.

The monarchy was overthrown in a 1969 coup, with Colonel Muammar Qaddafi seizing power and implementing a system of governance known as “Jamahiriya,” or the “state of the masses.” This was ostensibly meant to function as a novel form of direct democracy, where the people could directly govern through popular committees and conferences rather than parliamentary systems. While the system allowed people to directly participate in the process of governance on a local level, on a national level Qaddafi ruled unilaterally, violently suppressing opposition. There were virtually no political institutions under Qaddafi, as he expressed a strong ideological opposition to representative democracy and its associated bureaucratic inefficiency. Political parties were banned, and people were able to govern only through local committees. Furthermore, Libya had no constitution, independent judiciary system, or rights to free press.

The Jamahiriya system owed its notable longevity to rents from Libya’s vast oil wealth, which allowed Qaddafi to placate the people with generous social spending and socialist policies, a transactional governance relationship known as patronage. However, once he was overthrown, the Libyan people were left with vast oil reserves and no institutions in place to establish a central government. As a result, local communities and groups throughout Libya were left responsible for their own security, resulting in a proliferation of armed factions and militias.

There were an estimated 25,000 fighters in Libya during the 2011 revolution, and this number skyrocketed to 250,000 after Qaddafi was overthrown. These armed groups soon began to compete for power and influence, with many groups hoping to exert greater influence in the distribution of Libya’s oil wealth. Libya’s national army was largely destroyed in 2011 by rebel militias and NATO bombings, and without a national army, no group had the means to establish any type of national legitimacy, further contributing to the decentralization of Libya.

The Transitional National Council marked Libya’s first attempt to establish a central authority following the death of Qaddafi. It declared itself the sole legitimate government of Libya and appointed an interim administration to create a democratic constitution. However, the TNC itself was merely a coalition of local groups and militias, and without a national army or police force, its legitimacy was contingent on the cooperation of these militias. The transitional government was unable to dissolve these militias, so they subsidized them, placing them under the control of the ministries of interior. However, the TNC failed to properly incorporate these militias into formal military institutions, which emboldened these groups and triggered a competition among them for power.

The General National Congress faced similar issues, as it was also dependent on a coalition of militias for security. In addition, the GNC itself was quite fragmented, as the lack of formal political parties resulted in a broad-based coalition where the majority of representatives ran as independents. As a result, most of these elected independents represented the narrow interests of their respective local bases and tribes. Almost two thirds of independents were elected with less than 20% of the votes, with more than half of these independents winning less than 10% of votes. Six of the nine independents from Benghazi were elected on less than 2% of the votes, and each of these candidates represented local tribes.

Rather than a unified government for the whole of Libya, the GNC became a body where officials represented specific regions or groups of people, in effect playing a more federalist role than a central one. With no legitimacy and no monopoly on the legitimate use of force, clashes between armed groups and tribes continued to escalate, as did internal tensions between groups with competing interests. The controversial 2014 elections and subsequent supreme court decision left the country with two rival governments, each with ambiguous jurisdiction, further contributing to the fragmentation and continued conflict that has persisted to this day in Libya.

Libya’s attempts at creating a central government have resulted in a fragmented national security apparatus consisting of coalitions of localized militias vying for power and influence in their respective bases. This has translated into a precarious environment where certain groups have been known to kidnap elected officials and seize oil facilities for political leverage. This structure has provided incentives for these groups to consolidate power, as they are able to generate tax revenue and exercise political power within their bases. The interests of these militias represent the interests of the regions or tribes associated with them, rather than the national interests of all Libyans. So long as these militias are formed on the basis of regional, tribal, or religious ties, they will represent the interests of the regions or tribes associated with them rather than the national interests of all Libyans, precluding it from enjoying stability. Until a cohesive national army assumes power over localized militias, Libya will remain divided.

Foreign Intervention

- As Libya’s civil war has developed, several international actors have inserted themselves, turning the conflict into a proxy war. These foreign actors have thrown their support behind the rival governments of Haftar and Sarraj in the pursuit of their own interests, further complicating the dynamics of an already complex conflict. Some of these countries have become involved for ideological and religious reasons, while others have interests relating to oil, migration policy, counterterrorism, or most likely — some combination of these. One crucial accelerant of regional involvement has been the ideological contention between geopolitical rivals vying for influence on the question of political Islam. Foreign powers continue to ignore the 2011 UN-imposed arms embargo on Libya, and their involvement has only intensified the fighting, flooding the country with weapons, military equipment, troops, and mercenaries.

While the Government of National Accord is internationally recognized as the legitimate government of Libya, the majority of external actors have put their support behind General Haftar and the Tobruk government. This can largely be attributed to Haftar’s aversion to political Islam and the GNA’s ties to the Muslim Brotherhood. The United Arab Emirates have been a major source of support for Haftar, supplying him with advanced weapons, defense systems, and air support. The UAE staunchly opposes political Islam in any form, partnering with Haftar to curb its influence in the region. Islamic influence within the GNA has garnered Haftar support from Egypt, as well. The Muslim Brotherhood was outlawed and declared to be a terrorist organization by Egypt following the 2013 coup and overthrow of Mohamed Morsi, a member of the Brotherhood. The involvement and participation of the Muslim Brotherhood in the GNA has compelled Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi to align himself with general Haftar, who has tried to model himself as the “Sisi of Libya.” These countries, in addition to Saudi Arabia and Jordan, view the ideological currents of Islam within the GNA as a threat to their regimes.

While Islamist groups are represented in Tripoli’s government, their presence and influence are not as prominent as Haftar makes them out to be. Many Islamist groups in Libya, including the Muslim Brotherhood, are quite weak and loosely networked, but Haftar has benefited greatly from framing the GNA as being dominated by Islamists. Hypocritically, Haftar has aligned himself with the Madkhali Salafists, an ultra-conservative Islamic movement from Saudi Arabia. Madkhali fighters have reportedly been on the front lines of Haftar’s offensives, playing a crucial role within the Libyan National Army (LNA). This suggests that Haftar’s opposition to Islamic militant groups is more strategic than ideological. Regardless, it has also won Haftar the support of France, who formally supports the UN-backed GNA, but has covertly been providing Haftar with weapons and military support. France is geopolitically aligned with Emirati, Saudi, and Egyptian rulers in their regional rivalry with Turkey and Qatar, having provided them with billion-dollar arms deals. Macron sees his backing of Haftar as a means of combatting terrorism and the spread of Islamist militancy, both in the region and in Europe. France fears that instability in Libyan could spread and threaten French influence in the Sahel region, where thousands of French troops are deployed.

While French interests lie in combatting Jihadism, Italy has expressed concerns over mass migration through Libya, which serves as a proverbial “door” to Africa. Due to its proximity, many African migrants go through Libya to cross the Mediterranean and seek refuge in Italy and other parts of Europe. This has been an issue of great importance for Italy, which has received thousands of migrants fleeing Libya’s civil war. Italy sees Tripoli and the GNA as the path to Libyan stability, and Italian officials have condemned France for its support of Haftar. Nonetheless, Italian support has been more diplomatic than material.

Russia has also become increasingly involved in the Libyan conflict, providing Haftar with weapons, vehicles, and military support. This aligns with the Kremlin’s apparent initiative of expanding its reach in the Middle East and North Africa, as we’ve seen through Russian intervention in Syria. Russia sees Libyan instability as an opportunity to gain a foothold in the region and further expand its sphere of political and military influence. Last year, Russia blocked a UN Security Council statement calling on Haftar to halt his offensive on Tripoli. In addition, Russia has sent mercenaries from the Wagner Group to support Haftar militarily. The Wagner Group is a Russian private military contractor run by oligarchs with ties to Putin, essentially making the group an extension of the Russian military. These mercenaries have also seized oil fields in an attempt to block the GNA from resuming oil exports.

On the other side of the conflict, Turkey has been the most significant source of support for the GNA, providing weapons and crucial military support for the internationally recognized government. In April of 2019, Haftar’s LNA launched an offensive on Tripoli, eventually taking control of most of Libya and its oil fields. As fighting reached the outskirts of Tripoli and Russian involvement became clear, Turkey deployed troops at the start of 2020 to back the GNA, effectively reversing the LNA offensive and driving Haftar’s forces back east. This staunch support of the GNA reflects existing tensions between Turkey and several of the powers backing Haftar, including the UAE and Egypt. Turkey has been a leading proponent of political Islam and supported the Justice and Construction Party, an Islamist group within the GNA with ties to the Muslim Brotherhood. However, while Turkey is ideologically at odds with the Arab powers backing Haftar over the issue of political Islam, the motivation for Turkish support of the GNA is largely driven by oil interests in the Mediterranean, and consequently, a desire to counteract increased Emirati and Egyptian influence in the region, which would threaten these Turkish oil interests.

Economic interests have been a key motivator of foreign intervention in Libya, which has the largest oil and gas reserves in Africa. In 2019, Ankara and the GNA reached an agreement granting Turkey drilling rights in a contested seabed in the East Mediterranean. Greece and Cyprus also claim jurisdiction of this seabed, and this agreement has been contested by these neighbors, in addition to several other regional powers hoping to secure influence in the oil-rich region. Were Haftar to take control of Libya, economic coordination would likely be dominated by allies of the LNA, many of whom are hostile towards Turkey. Within Libya, most of the oil fields are located in the east and south of the country, giving Haftar the ability to block exports and essentially hold the Libyan economy hostage. While other interests are at play, the powers backing Haftar have this in mind in hopes of favorable oil contracts in the future.

Since Turkish forces reversed Haftar’s military offensive on Tripoli, the conflict has reached a standstill, with neither side able to make any significant gains. As long as foreign powers continue their involvement in Libya, the situation is unlikely to change. The conflict has become a proxy war, with everybody’s interests being represented except those of the Libyan people. These foreign actors have invested heavily in supporting these interests, which has only prolonged the fighting and made compromise less likely. Allies view the sunken cost of their interventions as too stark to retrench, much like the case of nearby Syria’s civil war. Foreign intervention in Libya has only served to sustain and prolong the conflict, and by complicating the interests of both governments, it has continued to contribute to instability.

Societal Cleavages

- Social cleavages have also played a role in driving Libya’s civil war. Many of these cleavages have either been created or deepened by Libya’s lack of a central authority, but the inverse has also been true. These divisions generally exist along religious, tribal, and regional lines, and the civil war has aggravated these tensions. There have been historic grievances in the east due to the perception of an unfair distribution of resources. Understandably, Tripoli would get a larger share of the resources as the capital city under Qaddafi, and Sirte was also awarded money and resources, as this was Qaddafi’s home base. However, most of Libya’s oil reserves lie in the east, and many felt they don’t get their fair share of that oil wealth. This marginalization has been responsible for some of the opposition from the east to the government in Tripoli.

Divisions between Islamists and secularists are also present, even if self-interest leads to exaggerations of the degree to which these divisions exist. However, one of the deeper cleavages within Libyan society has been the ascendancy of tribalism, a consequence of the decentralized nature of Qaddafi’s rule. Lack of representative government at the local level under Qaddafi spurred the conflation of tribal ties with politics at local levels, consequently expanding the influence and prominence of these tribes throughout Libya. The increased influence of these tribes has compelled the development of patronage networks and rent-seeking between tribes and governments, further fragmenting the country along tribal and regional lines. During the revolution, mobilization of groups often took place through tribal networks, and in the aftermath, many Libyans were forced to resort to their tribal ties to ensure safety and security under such instability. While foreign intervention and a lack of central authority have played a more significant role in driving this conflict, these tribal and regional cleavages have contributed to the instability that has plagued Libya since it’s revolution.

Predictions

The Libyan civil war has spanned nearly a decade and attempts to stabilize the country have been unsuccessful. This year, we have seen developments in peace talks between the different sides of the conflict, but it’s uncertain whether this progress will amount to anything meaningful. Following the reversal of Haftar’s offensive on Tripoli and the stalemate that has resulted, a ceasefire was agreed upon by both sides in August, and a permanent ceasefire was agreed upon in October. While Haftar’s militias have violated this ceasefire numerous times, it has generally been successful in slowing the conflict. Haftar lifted his oil blockade, allowing exports to rise back to near pre-war levels. Both sides reached a preliminary agreement on establishing a roadmap to holding presidential and parliamentary elections within 18 months, and Libyan delegates have agreed open land routes between many cities and regions throughout Libya. Perhaps most importantly, both sides have agreed to “establish a military subcommittee to oversee the withdrawal of military forces to their respective bases and the departure of foreign forces from the front lines,” according to Stephanie Williams, acting UN envoy to Libya. While these developments are promising, it seems too early to gauge how effective these peace talks will be. This paper will lay out three plausible scenarios for Libya in the coming three years based on the factors discussed above.

Prediction #1 – UN-led elections take place, Haftar is removed, fighting continues

In this scenario, the ongoing peace talks continue, and Libya is able to successfully hold elections in 18 months. While there is a great deal of disagreement between the rival governments, they share a common interest in Libya’s oil. The Tobruk government is in possession of most of Libya’s oil reserves, giving it significant leverage over the economy. However, as the internationally recognized government, the GNA has leverage with regards to being able to export oil to the international community. For this reason, I believe there is hope for Libya to successfully hold elections. However, in this scenario, I predict that once the new government takes place and the threat of Haftar is gone, rival militias and tribes will eventually begin to fight again, and the new government will fail to establish legitimacy among all parts of Libya, which will essentially be a repetition of the last two attempts at creating a government. Once Haftar is removed from the picture, many militias and armed groups in both the east and west of Libya will still be opposed to whatever government is put in place. Ultimately, the fact remains that Libyan society is highly fragmented, and this fragmentation has only been exacerbated by the war. Even with Haftar gone and a new government in place, militias likely won’t be eager to give up their power at the local level, and like the TNC, the new government will not be able to disarm these groups and effectively exercise control over the entire country. Militias will try to hold onto their power in their respective bases, and conflict between these groups will continue.

Prediction 2 – UN-led elections happen, there is tentative peace

This scenario also assumes the peace talks continue and elections successfully take place by the end of 2021. While I find this scenario to be the least likely of the three, it is a more optimistic prediction where Libya is able to attain a tentative peace. Libyan officials have shown some willingness to negotiate an end to the war, so this scenario is heavily contingent upon the withdrawal of forces from Libya by foreign actors. If the international community is effectively able to incentivize these countries to withdraw from Libya, stability and peace will be much more attainable. On November 18th, the US Congress passed the Libyan Stabilization Act, which according to Ted Deutch, the head of the Foreign Affairs subcommittee on the Middle East and North Africa, aims to “notify all parties to the conflict, including outside actors, of our support for diplomacy and our willingness to use sanctions against obstructive actors that undermine ongoing political talks and refuse to withdraw military arms and forces from Libya.”

While the UN has been largely ineffective in influencing the foreign actors intervening in Libya, the US and some of its European allies could potentially use their international influence to successfully pressure these actors to disengage. Efforts would have to be taken by the international community to support Libya in setting elections and fortifying institutions in order to bolster the legitimacy of the new government. While this will be difficult, I believe it could result in tentative peace in the country. While fighting will likely continue to some degree among tribes and localized groups, a new central government with enough legitimacy could pull the country together and put an end to the civil war.

Prediction 3 – Civil war continues

In this scenario, peace talks don’t end up being successful, as there seem to be too many factors that could undermine the process. Unfortunately, it seems to me that this is the most likely outcome. I doubt the ability of the international community to put an end to foreign intervention in Libya. The actors involved have committed a tremendous amount of money and resources to their efforts in Libya, and there is no agreement that will be able to satisfy the interests of everybody involved. Many may turn to more covert methods of providing support in order to pacify the international community. We’ve seen this in the case of Russia, where private mercenaries have been sent to Libya rather than actual Russian forces, affording Russia plausible deniability with regards to its involvement. Furthermore, these actors have already shown their willingness to ignore the UN, as they have done repeatedly by violating the 2011 arms embargo.

Aside from the issue of foreign intervention, several past attempts at elections have proven to be unsuccessful, and while possible, it seems unlikely that the Libyan people will have much faith in a new government. The fragmentation of the country presents another factor that could undermine the peace process, as many militias are likely to oppose the emergence of a central government. It seems improbable that all these different factions will disarm after six years of constant fighting and put their trust and security in the hands of a new central government, especially when past governments since 2011 have been unable to provide national security without the support of these militias. Additionally, the ceasefire seems tentative, and while it has been generally effective so far, Haftar has already violated the agreement on several occasions, and soon enough, one of these violations is bound to result in military escalation.

Conclusion

The Libyan Civil War is often lumped into conversations about the wider consequences of the Arab Spring, but it stands alone in the divergent trajectory of its experience; oil rich and ostensibly stable, held together by Qaddafi’s tenuous grasp only to see the aftermath of his ouster devolve into the tribalism and infighting that prevents democratic consolidation. Libya’s history of colonization gave its institutions the path dependent character of decentralization that was exploited by Qaddafi during his unitary rule and has made political consolidation so difficult in the aftermath of his downfall. Geopolitical prominence and natural resource wealth have led to an influx of proxy alliances and foreign intervention. Societal cleavages in the form of tribal, regional, and religious schisms have made cohesive overarching reform elusive. The future is uncertain for Libya, which remains in a state of ceasefire as UN-led negotiations attempt to lay a framework for stability. The most optimistic outcome would see elections by December of 2021. Less optimistic is the possibility of elections that take place but fail to win a legitimate mandate between contending factions. Most likely, however, peace talks will fail, undermined by the very factors outlined in this essay — reminiscent of Libya’s arduous but persistent journey towards democracy.

Sources:

Abdusamee, Mohammed. “War-Torn Libya’s Rivals Agree Path to Elections in 18 Months.” Bloomberg, November 11, 2020. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-11-11/rivals-in-wartorn-libya-agree-on-path-to-elections-in-18-months.

Al-Atrush, Samer, and Stepan Kravchenko. “Putin-Linked Mercenaries Are Fighting on Libya’s Front Lines.” Bloomberg.Com, September 25, 2019. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-09-25/-putin-s-chef-deploys-mercenaries-to-libya-in-latest-adventure.

Allahoum, Ramy. “Libya’s War: Who Is Supporting Whom.” Accessed November 11, 2020. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/1/9/libyas-war-who-is-supporting-whom.

AW. “Turkey Seeks to Expand Oil and Gas Drilling through Influence on Tripoli Government | AW Staff,” May 15, 2020. https://thearabweekly.com/turkey-seeks-expand-oil-and-gas-drilling-through-influence-tripoli-government.

AW. “UN Reiterates Call for Withdrawal of Foreign Mercenaries, Forces from Libya |,” April 11, 2020. https://thearabweekly.com/un-reiterates-call-withdrawal-foreign-mercenaries-forces-libya.

Cristiani, Dario. “Libya’s Economic Crisis: Bringing the Oil Sector Back on Track.” Jamestown, May 27, 2016. https://jamestown.org/program/libyas-economic-crisis-bringing-the-oil-sector-back-on-track/.

DeWaal, Alex. “The African Union and the Libya Conflict of 2011.” Reinventing Peace (blog), December 19, 2012. https://sites.tufts.edu/reinventingpeace/2012/12/19/the-african-union-and-the-libya-conflict-of-2011/.

Eaton, Tim. “Libya’s Governance Crisis.” Chatham House – International Affairs Think Tank, September 6, 2017. https://www.chathamhouse.org/2017/09/libyas-governance-crisis.

El-Gamaty, Guma. “Libya: Gaddafi Left behind a Long, Damaging Legacy.” Accessed November 20, 2020. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2016/2/17/libya-gaddafi-left-behind-a-long-damaging-legacy.

Fasanotti, Federica Saini, and Ben Fishman. “How France and Italy’s Rivalry Is Hurting Libya,” October 31, 2018. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/france/2018-10-31/how-france-and-italys-rivalry-hurting-libya.

Glenn, Cameron. “Libya’s Islamists: Who They Are - And What They Want | Wilson Center.” Wilson Center, August 8, 2017. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/libyas-islamists-who-they-are-and-what-they-want.

Kingsley, Patrick. “Libyan Politicians Sign UN Peace Deal to Unify Rival Governments.” The Guardian, December 17, 2015, sec. World news. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/dec/17/libyan-politicians-sign-un-peace-deal-unify-rival-governments.

Lacher, Wolfram. “Fault Lines of the Revolution: Political Actors, Camps and Conflicts in the New Libya,” May 15, 2013.

“Libya Profile - Timeline.” BBC News, April 9, 2019, sec. Africa. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-13755445.

“Libya’s NTC Hands Power to Newly Elected Assembly.” BBC News, August 9, 2012, sec. Africa. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-19183300.

McKernan, Bethan. “Gaddafi’s Prophecy Comes True as Foreign Powers Battle for Libya’s Oil.” The Observer, August 2, 2020, sec. World news. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/aug/02/gaddafis-prophecy-comes-true-as-foreign-powers-battle-for-libyas-oil.

Pack, Jason. “How Libya’s Economic Structures Enrich the Militias.” Middle East Institute, September 23, 2019. https://www.mei.edu/publications/how-libyas-economic-structures-enrich-militias.

Press, Associated. “Libya Supreme Court Rules Anti-Islamist Parliament Unlawful.” The Guardian, November 6, 2014, sec. World news. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/nov/06/libya-court-tripoli-rules-anti-islamist-parliament-unlawful.

Schlein, Lisa. “UN Mediator ‘Very Optimistic’ About Latest Steps in Libya Peace Talks | Voice of America - English,” October 21, 2020. https://www.voanews.com/middle-east/un-mediator-very-optimistic-about-latest-steps-libya-peace-talks.

Shadeedi, A.H.A., N. Ezzeddine, and Netherlands Institute of International Relations “Clingendael.” Libyan Tribes in the Shadows of War and Peace. CRU Policy Brief. Clingendael, Netherlands Institute of International Relations, 2019. https://books.google.ca/books?id=zAvLxgEACAAJ.

Staff, Reuters. “Libya’s Haftar Pulls Back East as Tripoli Offensive Crumbles.” Reuters, June 5, 2020. https://ca.reuters.com/article/us-libya-security-idUSKBN23C127.

Stephen, Chris. “War in Libya - the Guardian Briefing.” The Guardian, August 29, 2014, sec. World news. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/aug/29/-sp-briefing-war-in-libya.

Tankut Oztas. “Libya and the Salafi Pawns in the Game,” September 1, 2020. https://www.aa.com.tr/en/africa/analysis-libya-and-the-salafi-pawns-in-the-game/1697641.

Taylor, Paul. “France’s Double Game in Libya.” POLITICO, April 17, 2019. https://www.politico.eu/article/frances-double-game-in-libya-nato-un-khalifa-haftar/.

U.S. House of Representatives. 2020. "House Passes Bipartisan Bill To Address Libyan Conflict". https://teddeutch.house.gov/news/documentsingle.aspx?DocumentID=402892.

Warfalli, Ahmed Elumami al-, Ayman. “Poor Turnout in Libyan Parliament Vote as Prominent Lawyer Killed.” Reuters, June 26, 2014. https://ca.reuters.com/article/us-libya-election-idUSKBN0F000720140626.

Wehrey, Frederic. “Libya’s Bloodshed Will Continue Unless Foreign Powers Stop Backing Khalifa Haftar | Frederic Wehrey.” The Guardian, February 2, 2020, sec. Opinion. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/feb/02/libya-foreign-powers-khalifa-haftar-emirates-russia-us.

Winer, Jonathan M. “Origins of the Libyan Conflict and Options for Its Resolution.” Middle East Institute, May 21, 2019. https://www.mei.edu/publications/origins-libyan-conflict-and-options-its-resolution.

Zeb, Yasir. “NTC to Transfer Power to Newly-Elected Libyan Assembly August 8.” RS News, August 2, 2012. https://www.researchsnipers.com/ntc-to-transfer-power-to-newly-elected-libyan-assembly-august-8/.