The Power of African Activism: How the ANC and Umkhonto We Sizwe Defeated Apartheid

The unique struggle against apartheid in South Africa represents a remarkable chapter in African history, marked by the tireless efforts of the African National Congress (ANC) and, more specifically, its military wing Umkhonto We Sizwe (MK). This movement spearheaded the dismantling of an oppressive system of institutional racism and stands as a testament to the power of African-led initiatives. This essay will explore the decision to adopt a policy of violence to achieve racial peace, the convergence of regional and global support during the armed resistance period, and the pivotal role of Nelson Mandela in bridging the gap between regional and international activism, further amplifying the ANC’s cause. In analyzing these aspects, this paper sheds light on the power of Pan-Africanism and its impact on global human rights history. The democratic transition in South Africa symbolized a triumph not only for its people but also for the wider African continent, exemplifying the ANC's ability to forge strong alliances and unite diverse groups on the path to liberation.

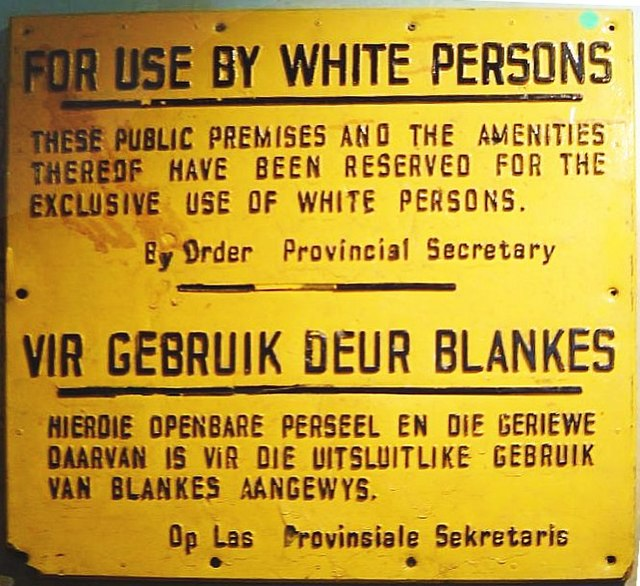

Apartheid policies in South Africa were racial segregation laws enforced by the National Party government from 1948 to 1994. These policies led to severe human rights violations against the majority Black African population, including forced removals from areas designated for white settlement, restricted movement, and the denial of basic civil liberties. Non-white populations were subjected to institutional racism, marginalization, and the destruction of their communities. Political dissent was suppressed, and activists faced imprisonment and torture. Before it was a political party, the ANC was the leading anti-apartheid movement in the country, mobilizing mass resistance and organizing protests under the leadership of Nelson Mandela.

The Sharpeville massacre, which occurred on March 21, 1960, marked a significant turning point in the ANC's shift in activism. During a peaceful demonstration in Sharpeville, South Africa, the police opened fire on the protesters, resulting in the deaths of approximately 69 people. This tragic event garnered worldwide condemnation and exposed the brutal nature of apartheid to the global community. In response, the South African government declared a state of emergency, detaining thousands of activists and banning several organizations, including the ANC. It was during this period of imprisonment that discussions surrounding armed resistance gained traction among the detainees as some members of the South African Communist Party (SACP) and ANC activists began contemplating it as a means to oppose apartheid. This growing wave of subversive activity was not lost on prominent ANC leaders like Nelson Mandela, who recognized the need to adapt their strategies in the face of escalating repression. In his famous speech on 20 April 1964 during his trial by the Supreme Court, he gave reasoned justification for the ANC’s choice to adopt a policy of violence, stating that “fifty years of non-violence had brought the African people nothing but more and more repressive legislation, and fewer and fewer rights.” He proclaimed that “experience convinced us that rebellion would offer the government limitless opportunities for the indiscriminate slaughter of our people. But it was precisely because the soil of South Africa is already drenched with the blood of innocent Africans that we felt it our duty to make preparations as a long-term undertaking to use force in order to defend ourselves against force.” The massacre catalyzed the ANC’s strategic direction, pushing them towards the formation of MK in the following years.

In terms of strategy and tactics, MK guerrillas generally avoided targeting civilians and employed violence in a more calibrated manner, adhering to a high standard Code of Conduct, which prohibited violence, assault, rape, cruelty, theft, drug use, and obscene language. MK leaders contemplated targeting State President PW Botha and his cabinet but decided against it due to the likelihood of civilian casualties, demonstrating a level of restraint in their actions. While the apartheid security forces derided MK guerrillas as “commuter bombers,” MK's claims of mauling the security forces were often exaggerated for propaganda purposes. Umkhonto We Sizwe played a significant role in discrediting and targeting the regime's governing structures during the State of Emergency in 1985, rooting out regime collaborators within black communities and fighting against apartheid proxy forces. From 1981 to 1983, MK conducted numerous high-profile attacks on government, military, and economic targets. These included the bombing of the SASOL oil-from-coal plant, the rocket attack on the Voortrekkerhoogte military headquarters, sabotage at the Koeberg nuclear power plant, and the bombing of the South African Air Force headquarters in Pretoria. These attacks received significant media attention and demonstrated MK's capacity for large-scale sabotage. The armed struggle waged by MK inspired and mobilized the population against apartheid, despite struggling to establish a visible presence within South Africa. Their recruitment efforts were based on kinship networks, extending beyond traditional hinterlands and encompassing urban areas. Their activities served as “armed propaganda,” exposing the weaknesses of the apartheid regime by transmitting the ANC's leadership to communities within South Africa, strengthening the ANC's credibility and symbolizing the liberation struggle. MK's armed struggle aimed to complement the ANC's mass struggle, and the movement adopted a policy of non-racialism and moral restraint.

The Front-Line States, including Tanzania, Angola, Zambia, Mozambique, and Zimbabwe, played a crucial role in providing sanctuary and support to the ANC and anti-apartheid activists during their years in exile. While these countries did balance the threats posed by apartheid South Africa, their support for the ANC and anti-apartheid activists went beyond mere strategic considerations. These impoverished African countries suffered significant economic losses and hardships for challenging apartheid, with an estimated $30 billion in lost development by 1988. The Front-Line States actively supported the ANC and anti-apartheid activists in various ways, including offering military training, logistical support, and diplomatic assistance. These states became bases for launching MK’s liberation movements’ operations against the apartheid regime and played a crucial role in sustaining the struggle. The apartheid regime, under President PW Botha's “Total Strategy” from 1979 to 1988, aimed at total militarization of South Africa's domestic and foreign policies. As part of this strategy, the regime engaged in destabilizing neighbouring countries by conducting raids in Zimbabwe, Botswana, Lesotho, and Swaziland and sponsoring proxy wars that led to the deaths of over 2 million people in Angola and Mozambique. The regional narrative of the struggle against apartheid offers a fresh perspective on African transnationalism, diverging from the conventional global solidarity framework.

Regional support can be understood through the lens of political culture and transnational activism. The theory of political culture, influenced by cultural sociology and neo-Marxist perspectives, emphasizes the importance of networks, groups, and institutions in shaping transnational political culture. The concept of “border thinking” offers insights into the dynamics of transnational activism by highlighting the significance of borders and boundaries in the context of globalization and colonial history. Movements and networks engage in practices that challenge fixed boundaries, including mobility, diaspora, and the construction of spaces that transcend borders. In the context of the armed resistance against apartheid, regional support involved activists and organizations crossing borders, establishing connections, and sharing experiences and strategies. The formation of MK solidified the ANC’s image as a revolutionary force committed to armed struggle, which resonated with many African countries and leaders engaged in anti-colonial and anti-imperial struggles. The solidarity between neighbouring countries and their active participation in supporting the ANC and MK reflected the shared goals of liberation and the rejection of racial oppression.

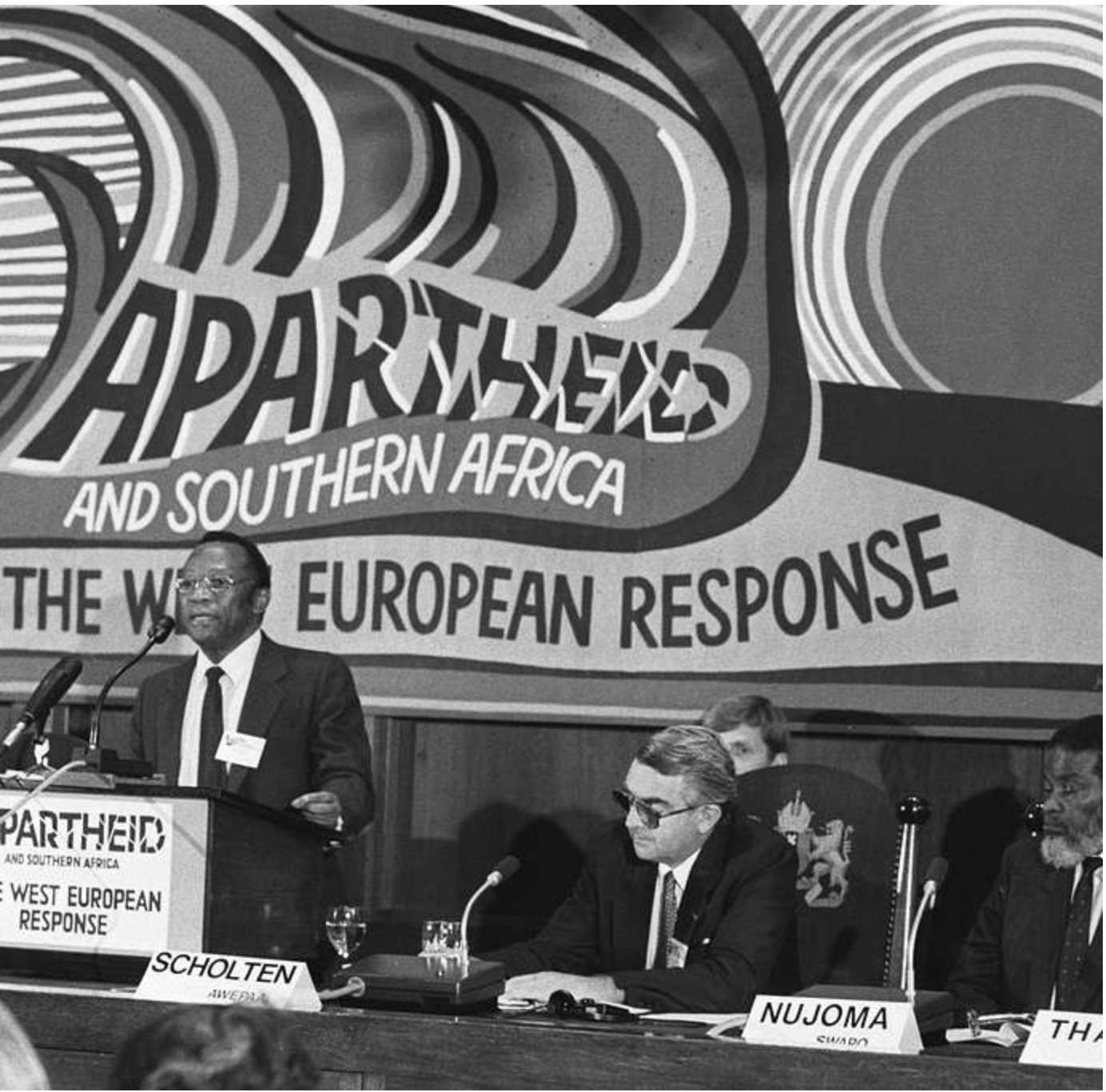

The emergence of international support played a transformative role in bolstering Umkhonto We Sizwe and its accomplishments in the fight against apartheid. Externally, the shifting balance of power and the end of the Cold War had a significant impact on ANC support. The negotiations between Western powers and the Soviet Union created an environment conducive to seeking solutions to conflicts in southern Africa. The removal of the “communist threat” that had helped sustain the apartheid regime's international position played a crucial role in changing perceptions and garnering support for the anti-apartheid cause. Additionally, the economic downturn experienced by South Africa during the 1980s was another factor. As the apartheid regime faced increasing financial challenges, international pressure mounted. The economic decline raised awareness of the injustices of apartheid and fueled solidarity movements around the world as the Boycott Movement in Britain mobilized public support and publicity for their consumer boycott of South African goods. The Special Committee against Apartheid, formed by ANC activist Razia Reddy, was a crucial node in the network of transnational anti-apartheid activism, providing well-researched information, financial support, and organizing conferences for representatives of anti-apartheid organizations. This allowed the ANC to increase their support and work towards the liberation of South Africa. Additionally, the advent of advanced communication technologies and the widespread dissemination of information played a vital role in mobilizing support for the anti-apartheid movement. From the 1980s, the transnational anti-apartheid movement relied heavily on mediated symbolic communication for organization and identification. The accessibility of global communication platforms allowed for the rapid spread of information, awareness, and coordination of efforts, resulting in increased international support for the cause.

Nelson Mandela's early involvement in the ANC and contributions to the anti-apartheid struggle played a significant role in establishing him as a representative figure of the organization. His unwavering commitment to justice and equality inspired people worldwide and galvanized support for the ANC, as his charisma, moral authority, and dedication to the cause made him an iconic figure of resistance against oppression. During his long imprisonment, Mandela became a focal point of international attention. The harsh treatment he endured in prison sparked outrage and fueled international campaigns for his release. The Nelson Mandela: Freedom at 70 campaign, initiated in the 1980s, mobilized global efforts to put pressure on the apartheid regime and secure Mandela's freedom. These movements played a vital role in raising awareness, organizing boycotts, and imposing economic sanctions against the apartheid regime. Once released, Mandela’s leadership during the negotiations with the apartheid government showcased his remarkable statesmanship and ability to bridge divides. Mandela's approach to reconciliation and inclusivity, as exemplified by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, emphasized healing and unity as the path forward for a post-apartheid South Africa. Instead of prosecuting the guilty as the Nuremberg trials had done for Nazi war criminals, he created the commission to grant pardons to those willing to reveal their crimes. Mandela's legacy as an inspirational leader and his commitment to justice and equality continue to resonate worldwide.

The ANC's strategic shift towards armed resistance through the formulation of Umkhonto We Sizwe ensured its long-term effectiveness and ultimate success. During the armed resistance period against apartheid, both regional and global support played significant roles in the struggle. Regionally, support from neighbouring countries was instrumental in providing sanctuary, logistical support, and military training for ANC activists. These Front-Line states actively engaged in the struggle against apartheid, despite the risks and economic hardships they faced. Networks of ANC activists formed, facilitating the exchange of ideas, resources, and strategies. The shared political culture rooted in colonial history and the rejection of racial oppression further solidified regional support. On the other hand, global support for the ANC and the anti-apartheid movement was driven by factors such as the end of the Cold War, the economic decline in South Africa, and the global proliferation of communication media. These factors increased global support for the ANC, mobilizing efforts such as international campaigns, boycotts, and economic sanctions against the apartheid regime. Nelson Mandela managed to bridge the gap between regional and international activism, as his message of forgiveness and healing resonated with people from different cultural, ethnic, and national backgrounds, earning him immense respect and admiration worldwide. His ability to unite diverse groups, engage with global audiences, and build alliances contributed significantly to the ANC's cause. The convergence of regional and global support played a crucial role in MK’s strategies and achievements, providing resources, amplifying their message, and creating a global movement that ultimately contributed to dismantling apartheid in South Africa.

Sources.

Douek, Daniel. “‘They Became Afraid When They Saw Us’: MK Insurgency and Counterinsurgency in the Bantustan of Transkei, 1988-1994.” Journal of Southern African Studies 39, no. 1 (2013): 207–25. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42001344.

Ellis, Stephen. “The Genesis of the ANC’s Armed Struggle in South Africa 1948-1961.” Journal of Southern African Studies 37, no. 4 (2011): 657–76. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41345859.

Lissoni, Arianna. “Transformations in the ANC External Mission and Umkhonto We Sizwe, C. 1960-1969.” Journal of Southern African Studies 35, no. 2 (2009): 287–301. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40283234.

Mandela, Nelson. “I Am Prepared To Die,” speech at the opening of the defence case in the Rivonia Trial, Pretoria Supreme Court, April 20, 1964, in The Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory, https://archive.nelsonmandela.org/za/sites/default/files/2021-08/IAPTD1.pdf.

Mathews, Kuruvilla. “Mandela’s Legacy: Some Reflections.” India International Centre Quarterly 41, no. 1 (2014): 38–51. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44733572.

Stevens, Simon. “Why South Africa?: The Politics of Anti-Apartheid Activism in Britain in the Long 1970s.” In The Breakthrough: Human Rights in the 1970s, edited by Jan Eckel and Samuel Moyn, 204–25. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt46nq77.14.

Thörn, Håkan. “The Meaning(s) of Solidarity: Narratives of Anti-Apartheid Activism.” Journal of Southern African Studies 35, no. 2 (2009): 417–36. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40283240.