The Hong Kong Revolt, Five Months and Counting

By Charles Madre

“What it boils down to is a fear by Hong Kong of coming under a Chinese system that seems ever more authoritarian, ever more repressive. That, of course, is a problem that Beijing does not know how to address.”

Nigel Inkster, International Institute for Strategic Studies (France24, 2019)

Since June, Hong Kong has been facing an unprecedented spate of political violence, with seemingly no end in sight. The current unrest was triggered by a proposed amendment to Hong Kong’s laws governing extradition. The amendment would allow for extraditions to anywhere by anyone on the basis of evidence provided by the requesting jurisdiction. There were widespread fears that Hong Kong’s political system would be incapable of denying anything China wished, meaning the Communist Party could effectively kidnap its opponents in Hong Kong. Fabricated evidence could easily be used to bring any Hongkonger to opaque and party-controlled courts across the border, ultimately breaching the “firewall” that had existed to separate the two very different legal systems practiced in Hong Kong and mainland China.

Protests initially took the form of ‘mega-marches’ which at one point attracted an estimated two million people. Despite the turnout representing an astonishing 27% of the population, the government chose not to give in to the demonstrators’ demands. This refusal was the immediate cause for escalation actions on the part of protestors, which elicited an ever more aggressive police response. On 1 July, protesters broke into and sacked the Legislative Council (LegCo) building, spray-painting demands onto the walls. On 21 July, protesters vandalized the façade of China’s Liaison Office (somewhere in between an embassy and Federal Government HQ) in Hong Kong as triads attacked and injured protesters, commuters and passers-by as police left the scene. On 5 August, half a million people participated in the largest general strike since 1989, triggering street battles with police. An estimated 1.7 million people rallied peacefully on 18 August. Since then, protesters have engaged in all out urban guerrilla warfare every weekend, hurling Molotov cocktails, bricks and slingshots while facing down tear gas, rubber bullets, water cannon and most recently, live ammunition (BBC, 2019).

Since 1 July, every protest has reiterated the “Five Demands of the People” agreed to on social media. They are:

• The complete withdrawal of the Extradition Bill

• The establishment of an independent commission of inquiry headed by a judge to investigate the entire saga

• The government to stop characterizing protests as “riots”

• The government grant an amnesty to all those arrested and charged since 9 June

• Universal suffrage for both the Chief Executive (CE) and LegCo (John, 2019)

It is therefore worth pondering how this cycle of violence sustained and strengthened over this summer of discontent.

Background

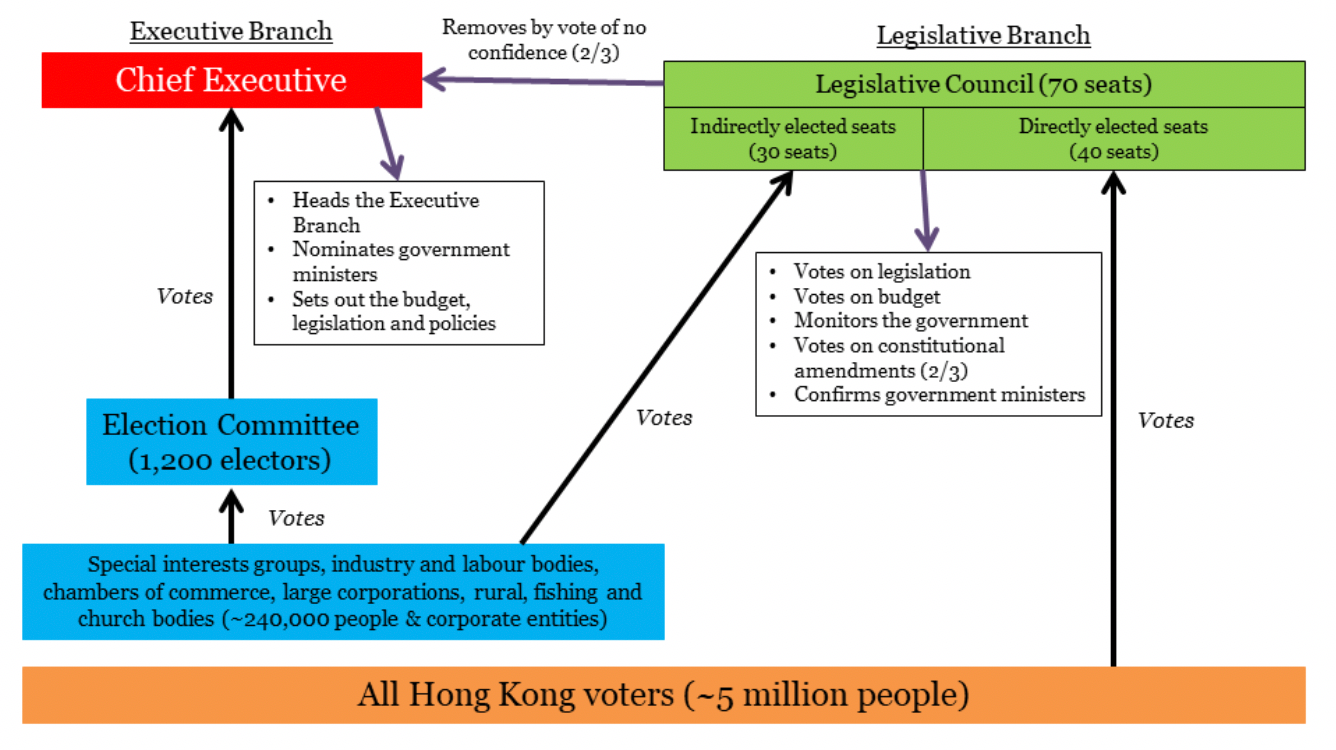

On 1 July 1997, Hong Kong’s sovereignty was transferred from the United Kingdom to the People’s Republic of China, ending 156 years of colonial rule. The Sino-British Joint Declaration that enabled the transfer, signed in 1984, provides that Hong Kong would be administered as a “Special Administrative Region” whereby existing political and economic structures in the territory would remain unchanged. Hong Kong would have a high degree of autonomy in all matters except foreign and defence. At least on paper, Hong Kong functions as a quasi-independent state. While it is ostensibly autonomous and a liberal pluralistic society, it is not democratic, and never has been. Democratic reforms have been proposed, as early as 1947, though progress has been strenuously slow. Today, the political system roughly looks like the following:

This democratic deficit demonstrated above is widely known and the need for reform is recognised across the political spectrum - the debate on the speed reform should take has been the dominant political issue in Hong Kong for the last 40 years. Since 1997, the popular vote in every legislative election was won by the Democrats. However, because of the rigged nature of the system, pro-Beijing forces have always held a majority of seats. This democratic deficit has fostered a culture of peaceful protest in Hong Kong. Given the public’s inability to have their voices reflected in government, protest turnouts have been seen as a barometer of public discontent. Government would then act accordingly and reverse unpopular policies. Demonstrations in support of universal suffrage have persisted in Hong Kong since the late 1970s. Most recently, Beijing’s proposal for universal suffrage in 2014 would transfer the Election Committee into a Nomination Committee, who would be charged with choosing “two to three” candidates that the public would then pick. In response, tens of thousands of students and supporters occupied major thoroughfares across the city demanding genuine universal suffrage without pre-screening. Carrie Lam, then Hong Kong’s number two, engaged in a dialogue with protest leaders. After nothing came out of the dialogue, infighting and loss of public support due to disruptions led the protests to fizzle out. In the following years, the government targeted and jailed the movement’s leaders. The government also began the practice of barring protest leaders from running for office under dubious legal grounds. While legal challenges have been launched against this practice, Hong Kong’s notoriously slow courts have not been effective in dealing with executive abuse.

Organised yet Leaderless

After the current movement spiralled out of the initial mega-marches in June, no one has come forward to be the public representative of the movement. Indeed, the organisers of the mega-marches, the Civil Human Rights Front (an organisation somewhat analogous to the ACLU in the US) have affirmed their role as a complementary voice to a territory-wide anti-government movement. Opposition lawmakers have taken a background role. Student leaders have only claimed to represent their respective student bodies. In fact, even the leadership of the Umbrella Movement in 2014 like Joshua Wong have not come forward to represent this current movement.

Indeed, the memory of Umbrella’s failure looms large in the back of every participant’s minds. This can be seen in discussion forums such as the Reddit-like LIHKG (the main platform for organising protest action) and message app Telegram. Social media users debate and vote on various forms of action. Ideas such as raising funds for a global ad campaign, forming human chains, occupying the airport, and calling a “citizens’ press conference” to counter the government narrative all originated on LIHKG. The platform has also served to rein in the most aggressive demonstrators. For example, when protesters beat up suspected Chinese spies at the airport, users noted that such actions could turn public opinion away from the movement. This was largely followed by the protesters. A similar case of self-reflection is currently taking place as demonstrators have begun torching and vandalising State-owned businesses and metro and police stations. The next days and weeks will shed light on whether LIHKG and Telegram can still serve this restraining role (Cheng, 2019).

Aside from deliberating on further action, LIHKG users have established a set of “values” that the protesters have quite universally adopted, the most important of which is “No Splitting” (不割席). They identified the main reason for the failure of Umbrella to be internal bickering between the Peaceful faction (和理非; lit. “peaceful, rational, non-violent”) and The Braves (勇武派); disagreements on the way forward in 2014 eventually led the movement to lose public support and fizzle out. As a result, “No Splitting” goes that factions may disagree on strategy, but neither faction will condemn or hinder each other from carrying out their method of protest. This ethos has even reached moderate opposition lawmakers and the Bar Association, who have repeatedly refused to condemn the use of violence at protests for fear of weakening the democracy movement (AFP, 2019).

Capitalising on the availability of social media platforms to deliberate on strategy has therefore allowed the movement to appear organised without any visible leader. The anonymity of the platform offers users some protection from legal and employment repercussions. It has also however led to risks of infiltration by government-backed agents provocateurs, though the effects of these alleged moles have been rather minimal so far.

Authorities at a complete loss on the way forward

After the street battles on 12 June, Carrie Lam suspended the Extradition Bill on 15 June. In the following few weeks, she made little to no public appearances as the protests escalated. Between her decision to suspend the Bill and her decision to formally withdraw it on 4 September, she repeatedly condemned the violence of the protesters but offered no concrete measures or strategy to end the unrest. Her repeated refusal to accede to the demand for an independent commission of inquiry despite many of her allies supporting the idea (Chung, Chiu, & Cheung, 2019) - ostensibly because it would damage police morale - is raising speculations that she may be taking orders from the police rather than the other way around.

Indeed, public trust in the police force is at an all time low. It is important to understand that Hong Kong is not accustomed to police brutality. Between 1967 and 2005, the police did not fire a single volley of tear gas at a public protest. Aside from openly lying in press conferences, particular egregious events, such as the use of tear gas on a peaceful crowd on 12 June, police inaction during the triad attacks on commuters in Yuen Long on 21 July, the rubber bullet shooting and blinding of a first aider on 11 August, the indiscriminate beatings of commuters on metro trains on 31 August and the shooting of the 11th grade boy with a live round in the chest have fueled hatred of the police force. The reputation of the force is further damaged by confirmed reports of undercover police officers dressed up as protesters (Yau, 2019) and sexual assault while in detention (Marlow & Li, 2019). Given the police themselves confirmed that undercover officers dressed up as protesters, many have posited that the worst protester violence was in fact committed by these undercover officers in order to discredit the movement. Whether true or not, public trust in the police force is so low that these sorts of allegations can become plausible in the eyes of citizens (Sataline, 2019).

For several months now, the options on the table for the government has been clear. Option 1 is the conciliatory approach. Giving in to the demands of the protesters, or at least variations of the demands, would quite swiftly end the demonstrations. Option 2 is to escalate the level of force. The Emergency Regulations Ordinance (ERO), a law dating from 1922, grants the Chief Executive Carrie Lam almost dictatorial powers in emergency situations. Through this law, Lam could grant far more powers to the police, censor news, prolong lawful detention times, impose a curfew and restrict individual rights. Lam has given in to one demand - formally withdrawing the Extradition Bill - although that has not stopped protesters from continuing to come out. On the other hand, she invoked the ERO to impose a ban on the wearing of face masks in public. Expectedly, this ban has been unenforceable as thousands continue to wear gas masks in large scale demonstrations, with police lacking the resources to arrest people by the thousands. While she could have gone further with more severe draconian measures, the risk to the economy restrained her authoritarian tendencies. Since then, the government has reiterated it has no plans to invoke the ERO again, fearing further damage to an already battered economy. Lam offered no solutions to the deadlock in her annual Policy Address on 16 October, which she delivered by pre-recorded video after she was heckled out of the legislature by opposition lawmakers, ignoring the burning streets outside to focus instead on housing subsidies, the construction of man-made islands and quantitative easing (Chan, 2019).

The complete lack of leadership on the part of the government has forced the police to be the point of contact between government and people. People who oppose the use of violence by the demonstrators have largely chosen to remain silent rather than be seen as apologists for an indefensible government. Arguments that protesters should voice their discontent through the ballot box fall on deaf ears given the widespread view that elections in Hong Kong are unfairly skewed towards pro-China candidates, with many popular opposition candidates not even being allowed to run for office. Indeed, many commentators who declared the movement would lose support after the Sacking of the LegCo building did not realise how much contempt there was for a legislature which since 1997 has been led by a pro-China coalition that lost the popular vote in every election since 1988. The lack of a democratic mandate and an abysmal record on policy has made it difficult for anyone to lend their trust to the current administration (Nauman, 2019).

The outlook

The protests are now approaching their sixth month. Despite the fact that the movement does not have a leader, social media has almost served the purpose of being a platform for direct democracy among the protesters, though concerns of adherence to decisions made online are rising. They have equally been sustained because of the lack of public trust in the police. Not only have incidents of police brutality been committed with complete impunity, but confirmed use of undercover police dressed up as protesters can easily lead to the conviction that the worst “protester” violence was in fact committed by police, in particular if the tactic was not supported on social media platforms. The government of Carrie Lam has also been completely incapable at finding a solution to the crisis. Her half-hearted attempts at appearing conciliatory by fulfilling one of the five demands have been overshadowed by her authoritarian measures to invoke the ERO and general appearance as a Beijing puppet and in the pocket of the economic elite, making it difficult for the movement’s opponents to publicly support the government. Interesting illustrations of such a view appeared in a letter to the South China Morning Post:

“Is it better to watch the leadership bury the city into permanent oblivion, or is it better to hope that the city might rise like a phoenix from the ashes of anarchy? We’re silent because there’s no good answer.” (Lhatoo, 2019)

How long will the movement be able to maintain the public support it has enjoyed in the last five months? Does the government and its masters in Beijing have the political ability to effectuate the radical reforms needed to begin regaining the trust of the public? Ultimately, only Beijing knows the answers to these questions. The Financial Times recently reported (Mitchell & Woodhouse, 2019) that its sources in Beijing believe the Communist Party is planning the process to replace Carrie Lam by March 2020. This news comes out of China meaning the report is obviously unverifiable, though it does not shed light on whether Beijing will change direction in its policies towards the restive territory. At the end of the day, what is known is that whether Hong Kong can rise like a phoenix from this spate of violence will indeed depend on the Communist Party’s willingness to let Hong Kong be Hong Kong.

Bibliography

AFP. (2019, October 14). ‘We will not sever ties’: Hong Kong violence prompts debate but no division among protesters. Hong Kong Free Press. Retrieved from https://www.hongkongfp.com/2019/10/14/will-not-sever-ties-hong-kong-violence-prompts-debate-no-division-among-protesters/

Chan, H. (2019, October 18). Hong Kong leader Carrie Lam explains policy address via Facebook Q&A, defends police. Hong Kong Free Press. Retrieved from https://www.hongkongfp.com/2019/10/18/hong-kong-leader-carrie-lam-explains-policy-address-via-facebook-qa-defends-police/

Cheng, K. (2019, September 11). Explainer: How Hong Kong’s ‘self-learning, open source’ protest movement decides what to do next. Hong Kong Free Press. Retrieved from https://www.hongkongfp.com/2019/09/11/explainer-hong-kongs-self-learning-open-source-protest-movement-decides-next/

Chung, K., Chiu, P., & Cheung, G. (2019, September 27). Adviser to Hong Kong leader Carrie Lam does not believe she has completely ruled out independent inquiry into police. South China Morning Post. Retrieved from https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/politics/article/3030620/adviser-hong-kong-leader-carrie-lam-does-not-believe-she

Hands tied and paralysed: Hong Kong leader struggles to end crisis. (2019, October 21). France 24. Retrieved from https://www.france24.com/en/20191021-hands-tied-and-paralysed-hong-kong-leader-struggles-to-end-crisis

John, T. (2019, August 30). Why Hong Kong is protesting: Their five demands listed. CNN. Retrieved from https://www.cnn.com/2019/08/13/asia/hong-kong-airport-protest-explained-hnk-intl/index.html

Lhatoo, Y. (2019, October 21). https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/politics/article/3033770/there-silent-majority-hong-kong-yearning-speak-out. South China Morning Post. Retrieved from https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/politics/article/3033770/there-silent-majority-hong-kong-yearning-speak-out

Marlow, I., & Li, F. (2019, October 11). Hong Kong Police Vow to Investigate Protester Sex Assault Claim. Bloomberg. Retrieved from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-10-11/hong-kong-police-vow-to-investigate-protester-sex-assault-claim

Mitchell, T., & Woodhouse, A. (2019, October 23). Beijing draws up plan to replace Carrie Lam as Hong Kong chief. Financial Times. Retrieved from https://www.ft.com/content/5ef0fc30-f4a3-11e9-b018-3ef8794b17c6

Nauman, Q. (2019, October 21). Hands tied: Hong Kong gov’t lacks power and experience to end protests, analysts say. Hong Kong Free Press. Retrieved from https://www.hongkongfp.com/2019/10/21/hands-tied-hong-kong-govt-lacks-power-experience-end-protests-analysts-say/

Sataline, S. (2019, September 1). From Asia’s Finest to Hong Kong’s Most Hated. The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2019/09/hong-kong-police-lost-trust/597205/

The Hong Kong protests explained in 100 and 500 words. (2019, October 14). BBC. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-49317695

Yau, C. (2019, October 9). Hong Kong MTR Corporation confirms plain-clothes police conducted checks inside closed Sheung Shui station after rumours officers dressed as protesters to damage facilities. South China Morning Post. Retrieved from https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/transport/article/3032228/hong-kong-mtr-corporation-confirms-plain-clothes-police