Persecution and Control: A Comparative Look at the Sodomy Laws in Iran, Lebanon, Egypt, and Tunisia

By Maeve McGuire

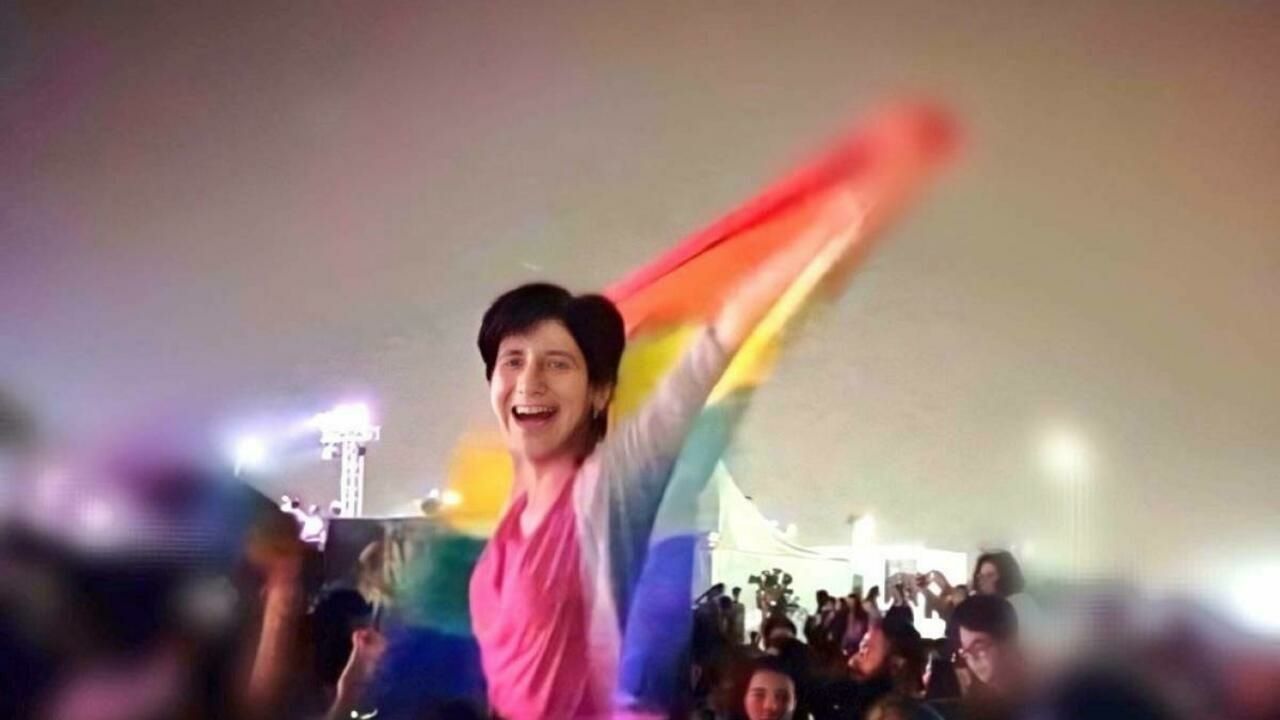

Cover Image By Hassene Drid (AP)

Introduction

The rights of LGBTQ+ individuals in the Middle East vary across the region, with complex state legal mechanisms and current socio-political landscapes underpinning distinct realities. Yet, sodomy laws are still a part of the legal codes of Iran, Lebanon, Egypt and Tunisia, and are employed to assert state dominance within society. Although their enforcement and penalties vary across the different cases, all of the aforementioned countries perpetuate intense political violence against their LGBTQ+ communities. Further, the sexualized nature of these laws and the specific wording of what constitutes these acts only further stigmatizes sexual minorities and plays into a perverse image created by the state to control its citizens and their identities.

The legal status of LGBTQ+ individuals within Iran, Lebanon, Egypt, and Tunisia share a similar foundation but are presented to varying degrees. While Iran, Egypt and Tunisia are more prone to enacting these laws to maintain an authoritative clamp on society, Lebanon rarely prosecutes under the sodomy law because it isn’t a state tool of domination. But the mere existence of sodomy laws within a state’s civil code normalizes persecution, humiliation, and violence against sexual minorities.

Legal Contexts: Prosecution and Their Supposed “Grounds” in Iran, Egypt, and Tunisia

Iran, Egypt, and Tunisia actively use the sodomy laws in their legal codes to prosecute LGBT+ individuals. To clarify, “same sex attractions, desires and identities” (Terman 2014, 34) are not illegal under sodomy laws, but a particular set of sexual acts that occur outside sanctioned heterosexual partnerships are.

These sodomy laws were born out of state anxieties and desire to control their citizenry to the fullest extent.

The verbalization of these acts are meant to humiliate sexual minorities, reducing them through state-sponsored sexualization. These sodomy laws were born out of state anxieties and desire to control their citizenry to the fullest extent, as these countries have a tenuous grip on their socio-political landscapes. Enforcement and punishment, however, varies between the countries, and are directed by state-specific contexts.

Iran

The Iranian legal system is based on Islamic jurisprudence, with religious scholars playing a prominent role in establishing and interpreting law. Supreme authority lies in the hands of the Velayat-e-Faqih, a religious institution that “guides” the elected parts of the state to assure that policy meets religious requirements. This institution has helped create Penal Code of 2013, in which homosexual acts are considered capital offenses, punishable even by death (Encarnacion 2016, 19). This state mechanism is one of the driving reasons that the code is brutally enforced. Iran is the most brutal compared to all the other countries in terms of punishment, employing other state actors such as the media to humiliate LGBTQ+ individuals. Those persecuted under sodomy laws are made a spectacle, dragged through the media, and even being publically punished. The most horrifying examples of this are public hangings of individuals charged under sodomy laws (Weinthal 2020). Violence against the accused is also encouraged by the legal system, as there are lenient laws with regards to honor killings by family members (Mendos, Botha, et al. 2020, 47). This includes small or nonesxistant punishments on family members who harass, abuse, or even murder somone that identifies as a sexual minority. These sodomy laws and way they are enforced reflect religious principles adopted by the state, as well as their anxiety about sex. Even the then-Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad denied the very existence of sexual minorities in Iran, stating that “we don’t have homosexuals [...] this does not exist in our country,” (Ahmadinejad 2007) to an audience at Columbia University in 2007. Ahmadinejad not only enforced dehumanizing laws to perpetuate violence against sexual minorities, but flat-out denied their very personhood, encapsulating Iranian policy towards sexual minorities.

Egypt

Egypt has similar legal codes with that of Iran, as they “enforce stigma and make the arrest and torture of [sexual minorities] possible” (Peletz 2006, 16) under sodomy laws. An event that highlights Egypt’s legal treatment of LGBT+ individuals in the Queen Boat incident, where dozens of men were arrested for “homosexual conduct” in 2001. These men were brutally tortured and hounded by the public, and their actions were emphasized as being the product of Westernization (Peletz 2006, 15). This enforcement of heteronormative behavior to protect their state identity is also seen in Iran, whose sexual minorities are met with similar treatment to those in Egypt. The subsequent public shaming is a state-technique shared with Iran, too, that highlights the dominance of the state within citizen life. Weaponizing the social stigma of being a sexual minority creates a dangerous environment for those who “deviate” from state norms. Where Egyptian legal codes diverges from Iran, however, is the theoretical basis of sodomy laws. The Egyptian law is not based on Islamic jurisprudence, but rather civil law passed in 2017 that bans “scandalous acts,” “debauchery or “prostitution” (Raghavan 2020) to persecute sexual minorities, enforcing the law to highlight the control of the state. Despite this theoretical divergence, both Iranian and Egyptian sodomy laws share the same purpose of controlling their citizenry, violating the rights of sexual minorities and encouraging violence against them.

Tunisia

Tunisia, although the only democratic country amongst the five case studies, shares the use of sodomy laws with the Egypt and Iran. Because of its status as a democratic country, the state faces more international backlash for their sodomy laws, but still upholds them in their legal code. Under Article 230 of the Tunisian Penal Code, “sodomy” is punishable by up to three years in prison (Khouili & Levine-Sproud 2017). Authorities buttress the continued use of the code against LGBT+ individuals on other provisions such as Article 226a, 228, and 231 in the Penal Code that criminalize “offences against public decency,” ‘indecent assault,” and “solicitation” or “prostitution” (Khouili & Levine-Sproud 2017). This legal language is similar to Egypt’s, where carefully selected, broad words are used to prosecute members of the LGBT+ community. Despite international and state backlash to these policies, Tunisia upholds them because of societal anxiety and desire to control citizens, mechanisms that are also found in Iranian and Egyptian policy. But unlike Egypt and Iran, the punishment for sodomy is considerably less detrimental, and there is no death penalty associated with these laws. But their existence still invalidates the rights of sexual minorities, despite there being a more open civil society in Tunisia to protest. Courts still actively sentence sexual minorities for sodomy and force them to undergo invasive procedures by authorities because of their identity, and until these laws are abolished, sexual minorities will live in constant fear.

They share the legal landscape that perpetuates state violence against the LGBTQ+ community.

Iran, Egypt, and Tunisia all share the same legal basis of sodomy laws, which are used to discriminate against sexual minorities within their countries. While the level of enforcement is based on state-specific factors, they share the legal landscape that perpetuates state violence against the LGBTQ+ community.

A Diverging Case: Legal Precedence and Lebanese Non Persecution

Lebanon has a flourishing LGBTQ+ community that is extremely active in civil society. They have made significant inroads within their community in terms of treatment and opportunities for sexual minorities, and are integral members of the socio-political landscape. Lebanese treatment of LGBTQ+ individuals is vastly different compared to Iran, Egypt, and Tunisia, yet the mere fact that there is sodomy laws in the legal code creates a anti-LGBTQ+ state climate that perpetuates political violence as long as they remain in the code.

Lebanon

While the legal status of LGBT+ individuals in Lebanon is technically illegal, the country rarely enacts their discriminatory legislation. The country’s Criminal Code 534 penalizes “unnatural” (Hanssen & Safienddine 2016, 210) sexual intercourse, like Tunisia, Iran, and Egypt, but is rarely used to prosecute. The punishment itself is also less severe than in Tunisia, Iran, and Egypt: the 2001 Code of Criminal Procedure outlines that sentences of less than one year are not implemented. This is for a variety of state-specific reasons, including Lebanon being a more secular government compared to Iran. Article 534, the legal basis for discriminating against sexual minorities, is rarely enacted by the state because of the state’s more secular nature, with fewer than ten prosecutions under it according to Helem, a LGBT+ Rights Organization based in Lebanon (Canada: Immigration and Refugee Board 2014). Further, there is also a more vibrant LGBT+ population in Lebanon that exercises more freedoms such as speech or assembly compared to other countries. These protections, along with a vibrant civil society, means that the state is less motivated to persecute individuals under sodomy laws becuase of the backlash they would face.

Recent legal rulings in Lebanon have given hope to extended protections for sexual minorities. There has been major breakthrough in a 2018 District Court ruling that states that “consensual sex between people of the same sex is not unlawful.” (Human Rights Watch 2018) Even more recently, Lebanon’s top military prosecutor ruled that same-sex acts are not criminal acts in 2019, disputing the claim that they constitute “unnatural sexual relations” (Strenski 2020, 381). Because the code containing sodomy laws is so vague, there has been discrepancies in sentencing, such as the 2015 case where nine people suspected of being gay or transgender were acquitted under charges of the Article because the judge ruled that homosexual acts were not considered unnatural. Legal loopholes and precedence make prosecution more unlikely compared to the more targeted policies of Iran, Egypt, and Tunisia.

Yet, even the mere existence of sodomy laws is an act of political violence against sexual minorities. Comparatively, the LGBTQ+ community has a better quality of life, but the state still maintains a violent framework against them. Legal prosecution changes over time, and just because there have been breakthroughs and prosecution under sodomy laws has waned in recent decades, doesn’t mean that it is impossible to be sentenced in Lebanon because of your identity. relying solely on the whim of a judge is tenacious at best, and even undergoing the process is humiliating. Lebanon still uses sodomy laws to control society, as the legal framework still exists to persecute sexual minorities. This threatens the community, perpetuates stigma, and controls the actions of activists who still live under threat.

Conclusion

All four countries have a legal framework that incites political violence against sexual minorities. While there are differences in prosecution, punishment, and use, all of the sodomy laws serve the purpose of controlling the states and the actions of its citizenry. Until the sodomy laws are repealed, there will be a legal blueprint to shame, intimidate, and control the citizens of Iran, Egypt, Tunisia, and Lebanon.

In Memory of Sarah Hegazi, LGBTQ+ activist and survivor. Hegazi, a native Egyptian, was imprisoned in 2017 after waving a rainbow flag at a concert in Cairo. She was charged for "inciting acts of immorality or debauchery," and held for three months. During her imprisonment, she undergone horrific torture at the hands of the Egyptian authorities, and even after she escaped, she felt that she was “still stuck in prison.”

After Hegazi escaped to Canada following her imprisonment, she became a vocal activist within the Toronto area. Throughout her life, she used her platform to highlight the abuses the Egyptian LGBTQ+ community have undergone, including prosecution under sodomy laws.

May she always be remembered.

Bibliography

Boisvert, Nick. LGBTQ Activist Sarah Hegazi, Exiled in Canada After Torture in Egypt, Dead at 30. CBC News, cbc.ca, June 16, 2020. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/sarah-hegazi-death-1.5614698.

Canada: Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada. Lebanon: Situation of sexual minorities in Beirut, including treatment by society and the authorities, legislation, support services and organizations that provide assistance (2010-2013). January 9, 2014. https://www.refworld.org/docid/530378a44.html.

Encarnación, Omar G. “The Troubled Rise of Gay Rights Diplomacy.” Current History 115, no. 777 (2016): 17–22. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48614128.

Hanssen, Jens, and Hicham Safieddine. “Lebanon’s ‘Al-Akhbar’ and Radical Press Culture: Toward an Intellectual History of the Contemporary Arab Left.” The Arab Studies Journal 24, no. 1 (2016): 192–227. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44746852.

Khouili, Rami and Daniel Levine-Sproud. “Why does Tunisia Still Criminalize Homosexuality?” Heinrich Boll Stftung Tunisie, tn.boell.org, October 30, 2017, https://tn.boell.org/en/2017/10/30/why-does-tunisia-still-criminalize-homosexuality.

Mendos, Lucas, Kellyn Botha, Rafael Lelis, Enrique López de la Peña, Ilia Savelev, and Daron Tan. State-Sponsored Homophobia 2020: Global Legislation Overview Update (Geneva: ILGA, December 2020).

Peletz, Michael. “Transgenderism and Gender Pluralism in Southeast Asia since Early Modern Times.” Current Anthropology 47, no. 2 (2006): 309–40. https://doi.org/10.1086/498947.

Raghavan, Sudarsan. “Arrests and Torture of Gays, Lesbians in Egypt are ‘Systematic,’ Rights Report Says.” The Washington Post, washingtonpost.com, October 1, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/middle_east/egypt-lgbt-abuse/2020/10/01/424badbc-03c7-11eb-b92e-029676f9ebec_story.html.

Strenski, Ivan. “On the Jesuit-Maronite Provenance of Lebanon’s Criminalization of Homosexuality.” Journal of Law and Religion 35, no. 3 (2020): 380–406. doi:10.1017/jlr.2019.42.

Terman, Rochelle. “Trans[Ition] in Iran.” World Policy Journal 31, no. 1 (2014): 28–38. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43290423.

Weinthal, Benjamin. “Iran Publicly Hangs Man on Homosexual Charges.” Jerusalem Post, jpost.com, April 12, 2020. https://www.jpost.com/middle-east/iran-publicly-hangs-man-on-homosexuality-charges-578758.

Zengin, Aslı. “Sex for Law, Sex for Psychiatry: Pre-Sex Reassignment Surgical Psychotherapy in Turkey.” Anthropologica 56, no. 1 (2014): 55–68. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24469641.

“Lebanon: Same-Sex Relations Not Illegal,” Human Rights Watch, hrw.com, July 19, 2018, https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/07/19/lebanon-same-sex-relations-not-illegal.