Studying Development Through the Lens of Corruption: An Anthropological and Economic Perspective

With the end of the Second World War came the beginning of the era of development. “What we envisage is a program of development based on the concepts of democratic fair dealing,” declared President Truman in a speech to Congress (Esteva 2009, 1). The Marshall Plan could arguably be considered the first official development package to exist, but it would most certainly not be the last. New subfields of social sciences would concentrate on studying and analyzing development as a historic and present solution to fight poverty.

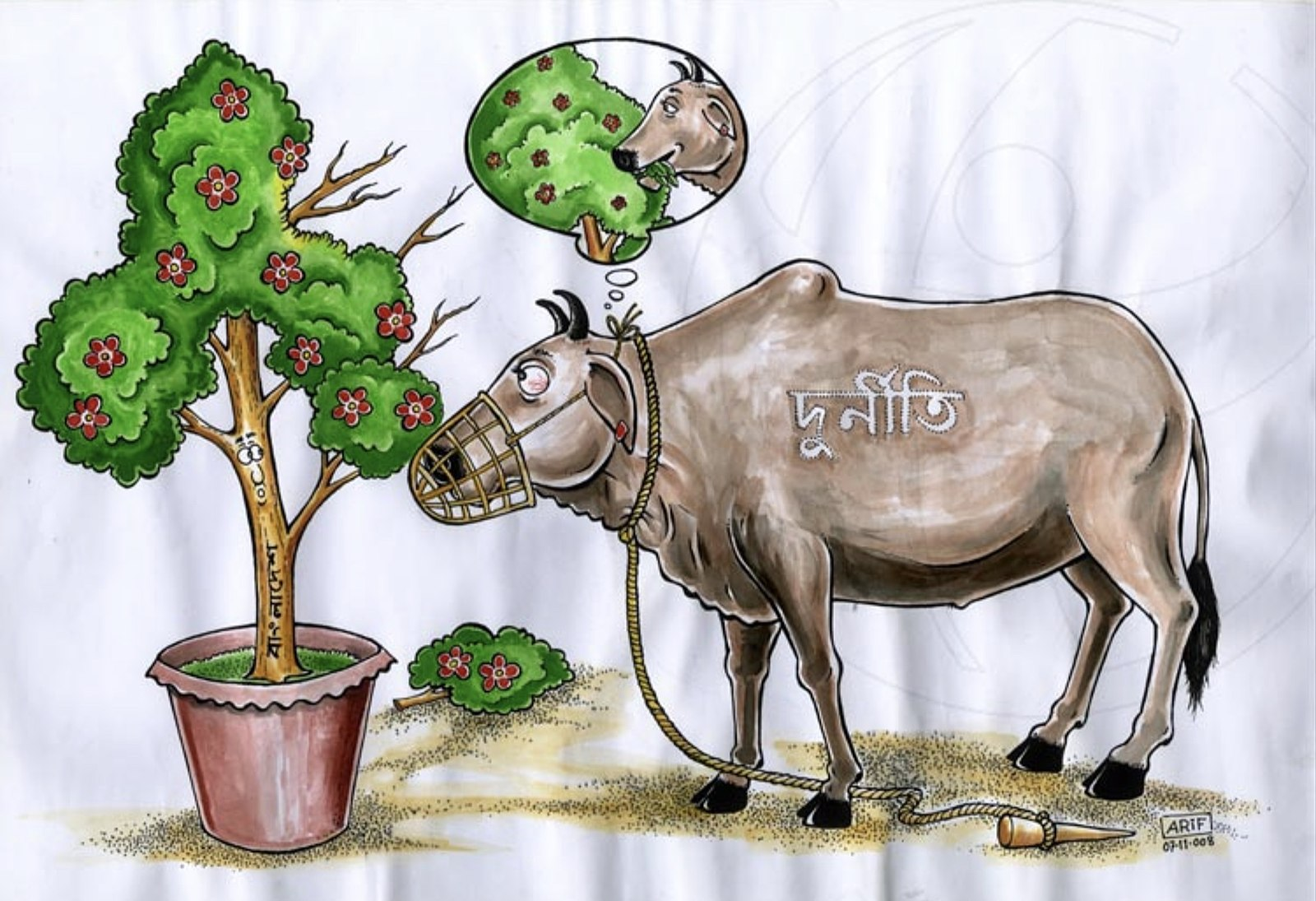

Economics and anthropology have had their fair share of scientists from their respective fields study development but through very different lenses. In fact, although both economists and anthropologists study development, often together, they have different methods of analyzing and understanding it as an academic subfield. These distinctions will be presented by reviewing academic literature from both fields of study. Corruption, that is “the sale by government officials of government property for personal gain,” will be used as a sort of case study to understand how Anthropology and Economics are distinct in their approach to development studies (Shleifer & Visknhy 1993, 599).

Corruption and Development: Anthropology

In his article “Blurred Boundaries: The Discourse of Corruption, the Culture of Politics, and the Imagined State,” Akhil Gupta creates “an ethnography of the state” to analyze corruption in India (Gupta 1995, 375). He bases his work on fieldwork he conducts in a small north Indian village he calls Alipur. Gupta begins by analyzing the encounter of the citizen with the state at the local level: “For the majority of Indian citizens, the most intermediate context for encountering the state is provided by their relationships with government bureaucracies at the local level” (Gupta 1995, 378). Interaction would be done either using the physical space of government to discuss with fellow citizens or to use the services provided in that space.

Either way, corruption was a component. On the one hand, citizens use the space as a place where “corruption was discussed and debated” while on the other hand, corruption is a complete component to local state mechanisms (Gupta 1995, 378). Gupta turns his attention to Sharmaji who is a patwari: “an official who keeps the land records of approximately fix to six villages” (Gupta 1995, 379). The author explains that transactions between villagers are done in a transparent fashion in front of the patwari though it is evident to all citizens that “these things “cost money,” [and] in most cases the “rates” were well-known and fixed” (Gupta 1995, 379). Usually the amount given, Gupta explains, is relatively small at such a local level, so the bureaucrats make their money off volume unlike public servants in higher levels of government.

The author then turns his attention to the discourse of corruption in public culture. Gupta argues that “the analysis of reports in local and national newspapers tells us a great deal about the manner in which “the state” comes to be imagined” including perceptions on corruption (Gupta 1995, 385). He goes on to explain how corruption played a huge role in national politics in the 1980s and how Rajiv Gandhi’s election in 1984 “was fought largely on the slogans of the eradication of corruption” (Gupta 1995, 386).

He continues by analyzing local and national newspapers to better understand the collective societal perception of corruption in India. Gupta finally turns to what he calls the imagined state: “The government […] is being constructed […] in the imagination and everyday practices of ordinary people” (Gupta 1995, 390). To analyze the imagined state, he interviews Ram Singh and his sons who are prosperous yet part of a lower cast from Alipur. Essentially, Akhil Gupta analyzes corruption through an often-used manner by anthropologists of case studies in the hope to find generalizations which can then serve further research in the field.

Unlike Gupta, Ravi Sundaram approaches the anthropological study of corruption in a more holistic way. He discusses how India’s urban reality is shaped by its postcolonial identity and how its urban modernity “has pushed urban discourse in new directions” (Sundaram 2021, 1). The author focuses on “the materialization of new technologies in Indian cities” and how they will affect not only governance and state, but also culture and lifestyle (Sundaram 2021, 3). There is a discussion on what the author calls ‘pirate modernity’ which depends on informal arrangements. It is a modernity that can be viewed as recycled while simultaneously commoditized.

Although the article deals mainly with how India’s colonial past affects how modern urban governance functions, there is a part allocated to transparency. Sundaram explains how the postcolonial city after information “brings both urban space as well as documented populations in the domain of the visible” (Sundaram 2021, 6). “Transparency has become one of the main slogans of urban and national politics for the Indian middle class, culminating in the anti-corruption campaigns in 2011-12” but that does not mean that corruption is not a component to Indian bureaucracy (Sundaram 2021, 5).

Nonetheless, improvements have been made, notably with the creation of the landmark Right to Information Law which allowed citizens to have access to documents within 30 days before civil servants would face a pay cut. As Sundaram puts it “While not all RTI requests were about corruption, they helped place transparency at the heart of public discourse, helping a liberal agenda around information culture and the modernization of urban governance” (Sundaram 2021, 6). It led to secrecy being associated to corruption and, in the desire for less secrecy, a decrease in corrupt behaviour by the State occurred. The Income Tax department also began using permanent account numbers for all taxpayers in the hope of reducing tax evasion. Essentially, what Sundaram displays in the article is how technology allows for a change in postcolonial institutions prone to corrupt behaviour.

Corruption and Development: Economics

Olken & Pande “review the evidence on corruption in developing countries […] focusing on three questions: how much corruption is there, what are the efficiency consequences of corruption, and what determines the level corruption?” in their article “Corruption in Developing Countries” (Olken & Pande 2012, 479). The article firstly analyzes the magnitudes and efficiency costs of corruption. Olken & Pande point out that “there are remarkably few reliable estimates of the actual magnitude of corruption, and those that exist reveal a high level of heterogeneity” (Olken & Pande 2012, 481). Corruption can either be studied through perception, surveys, estimates from direct observation, graft estimation by subtraction, and estimations from market inferences to name a few.

Another approach is by using equilibrium conditions in the labor market (Olken & Pande 2012, 486). The article then turns to the question of if corruption matters. Olken & Pande argue that “corruption could either have efficiency costs or lead to efficiency gains” (Olken & Pande 2012, 491). Continuing, the article explores what determines corruption and what would incentivize bureaucrats to take bribes. The authors present a mathematical formula to explain the situation where the bureaucrat is better off by taking the bribe (Olken & Pande 2012, 496). Transparency and punishment are viewed as ways to combat corruption. In the end, the article attempts to objectively present the economic theories which can explain issues of efficiency, regulation, and corruption.

Similar to Olken & Pande, Paolo Mauro analyzes corruption through a macroeconomic lens while focusing on data-oriented conclusions. In “Corruption and Growth,” Mauro analyzes “a newly assembled data set consisting of subjective indices of corruption, the amount of red tape, the efficiency of the judicial system, and various categories of political stability for a cross section of countries” (Mauro 1995, 681). In the introduction, the author explains how most economists agree that corruption causes economic inefficiency but that “some authors have suggested that corruption might raise economic growth” (Mauro 1995, 681).

Mauro’s work finds “that corruption lowers private investment, thereby reducing economic growth” (Mauro 1995, 683). The rest of the article describes the data from developing countries he uses to come to that conclusion including indices such as the Business International Indices of Corruption and Institutional Efficiency, the Bureaucratic Efficiency Index, and the Index of Ethnolinguistic Factionalization. In the end, Mauro finds a negative relation between all three mentioned indices above and the rate of investment, justifying that corruption is negatively correlated to economic growth (Mauro 1995, 695). However, the author mentions that “there is only weak support for the hypothesis that corruption reduces growth by leading to inefficient investment choices” thus hinting at a relationship perhaps stronger than a simple negative correlation between corruption and investment. In all, Mauro uses empirical data and macroeconomics to argue that corruption has a negative effect on economic growth.

Conclusion

Both anthropology and economics study development though through completely different lenses. What the literature shows is contrasting ways in approaching development studies by the two social sciences. Anthropology is case study oriented, often focusing on the individual rather than the whole of society. As was displayed in Gupta’s reading, personal interviews and individual encounters make up the content used to then further research and eventually generalize patterns in the developing world. Nonetheless, this does not mean that a global view cannot be researched through Anthropology. In fact, Sundaram’s study on India allows for generalizations and a better understanding of Indian society and its view on bureaucracy and corruption. Through analysis of past and current events, anthropologists study development with a greatly humanistic approach which must be valued. On the other hand, Anthropology lacks more of the concrete data needed to end up with scientific generalizations.

Where Anthropology lacks is where economics thrives when discussing development studies. Economic development studies are heavily concentrated on quantifiable data and macroeconomic models which can then be used to come to a scientific conclusion. In Olken & Pande’s work, attempts to quantify perception are key to understand how corruption functions in the developing world. They depend on mathematics to rationalize the observations made and to come to a conclusion which can then be generalized. In fact, Paolo Mauro simply presents his hypothesis – that corruption negatively affects economic growth – and proves it correct by running regressions and seeing if there indeed is a negative significant correlation between a certain corruption index and investment. Very little of all this is human or personal and this is probably the biggest difference between the anthropological and economic study of development.

Corruption is an issue in developing countries as it obliges people who may not have much to pay for services the State should be able to provide with tax revenue. Many social scientists – both anthropologists and economists – agree that corruption allows for an unfair and inefficient economic context in frequently already dire situations in the developing world. Though the two sciences differ much in their approach to studying development, as is shown when using corruption as an template, they simultaneously bring forth a unique perspective which allows for a more complete and just research analysis. To sum up, anthropologists can learn to be more objective and quantitative in their study while economists can adjust to add more humane and qualitative components to their subfield of economic development. Both sciences have much to share with one another, especially when both scientists and subjects of the research done in the developing worlds are to surely benefit form such cooperation.

Works Cited

Esteva, Gustavo. 2010. “Development”. In The Development Dictionary a guide to knowledge as

power, edited by Wolfgang Sachs. London & New York: Zed Books, pp. 1-23.

Gupta, Akhil. 1995. “The Discourse of Corruption, the Culture of Politics, and the Imagined

State”. In American Ethnologist, Hoboken: Wiley on behalf of the American Anthropological Association. pp. 375-402.

Mauro, Paolo. 1995. “Corruption and Growth”. In The Quarterly Journal of Economics, August

1995, Oxford: Oxford University Press for Harvard University Department of Economics. pp. 682-712.

Olken, Benjamin A., and Rohini Pande. 2012. “Corruption in Developing Countries”. In The

Annual Review of Economics 2012. 4, Palo Alto: Annual Reviews. pp. 479-509.

Shleifer, Andrei, and Robert W. Vishny. 1993. “Corruption”. In The Quarterly Journal of

Economics, August 1993, Oxford: Oxford University Press for Harvard University Department of Economics. pp. 599-617.

Sundaram, Ravi. 2021. “The Postcolonial City in India. From Planning to Information?”. InTechniques & Culture no 67, Paris: Éditions de l’EHESS. pp. 1-15.