“Refusal to Vanish”: An Intersectional Examination of Cultural Healing in Indigenous Contemporary Art

Charlotte Pierrel is a McGill graduate with a B.A. in Art History and Psychology, currently pursuing graduate studies at The University of Edinburgh.

Content warning: This article contains mentions of trauma, colonial genocide and gendered violence against Indigenous peoples that can be disturbing or triggering.

Introduction

The works of contemporary Anishinaabe artist Rebecca Belmore and Métis artist Christi Belcourt are powerful declarations of protest against the ongoing violence towards Indigenous women. A visual battle cry against systemic racism and abuse, their art pays tribute to the 1,200 or more Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW) in Canada. Belmore’s 2008 photograph and billboard Fringe (Figure 1 and 2) reflects these acts of brutality in a visibly mutilated Native body, while Belcourt’s 2012 commemorative installation Walking With our Sisters (WWOS, Figure 3) features 1725 vamps, each pair representing a lost life. Both works make public an epidemic largely ignored and compounded by failures of federal government to protect Native women. The intention of the artists is to render their invisibility palpably visible by addressing the collective amnesia rooted in gendered legacies of colonialism that have naturalized physical and sexual violence against Indigenous women.

The interconnectedness of gender, geography, and indigeneity inherent in these artworks demand intersectional and postcolonial art historical approaches. Contemporary Indigenous women artists Belmore and Belcourt both use the body as a metaphor for resistance. With the use of traditional beadwork for signaling resilience and healing, the public nature of these installations simultaneously work as land acknowledgements, highlighting the spiritual dimension of Indigenous land rights.

Body as Resistance

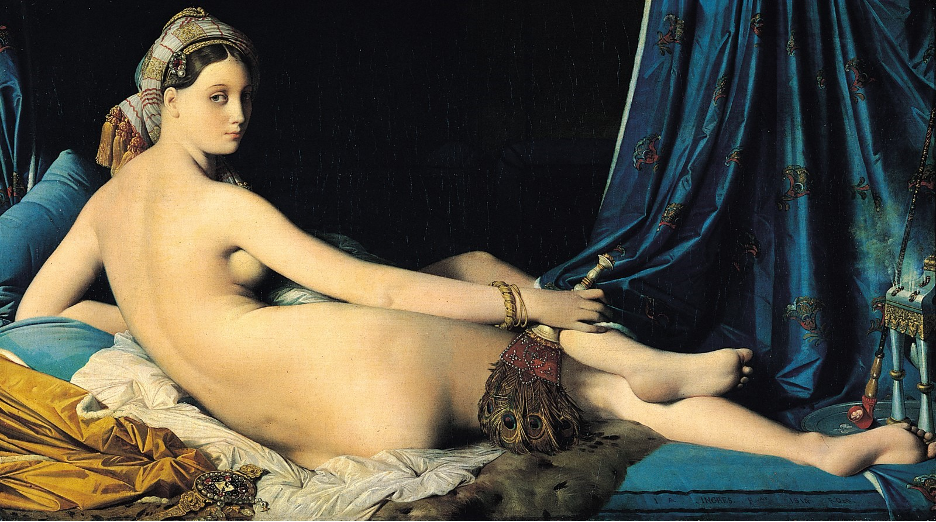

The physical body in the context of colonialism is deeply entangled with legacies of domination and violence. Fringe focuses on the ongoing presence of the surviving body while WWOS highlights its gaping absence. Belmore’s work features a naked woman lying in a semi fetal position facing away from the viewer, a white drape shielding her lower body. A deeply shocking laceration runs diagonally across the length of her back and yields rivers of crimson blood. Upon closer examination, the blood dripping from the stitched wound reveals intricately fringed beaded threads. Limiting readings interpret the figure as a cadaver which follow colonial practices of inscribing “fatal signs of mortality upon Indigenous bodies.” Belmore however, states that the “wound is on the mend…She will get up and go on.” Indeed, the white drape recalls Christ’s loincloth, signaling a resurrection and the beaded fringe resembles the traditional Métis sash, a symbol of resistance which pays tribute to the spiritual message of Luis Riel. Belmore also uses the body to push back against colonial framings of Indigenous women as sexually available, denouncing the disproportionate violence directed at Indigenous prostitutes. Government policies such as the Indian Act (1867-1951) particularly affected Indigenous women by denying them status rights, making them physically and economically vulnerable and often leaving them little choice but to resort to prostitution. Reappropriating the ‘exotic harem nude’ from Ingres’s 1814 Une odalisque (Figure 4), her figure utterly subverts the Indian Princess stereotype. Turning her back on the trauma she has experienced, and on its perpetrators, she refuses to be subordinate to the desires of the white male gaze. She rejects the “naturally promiscuous” colonial label which has justified her “violent exploitation.”

Native female bodies in Belcourt’s work, on the other hand, are painfully conspicuous in their absence. No longer able to physically be there, the installation’s space echoes the inability to rematerialize absent bodies and the government’s failed responsibilities. Detached from their intended purpose as part of moccasins, the 1762 handmade vamps embody each MMIW, which Anderson explains “remain as fragmentary and incomplete testimonies to the unfinished lives they represent.” The impact of the vast pathways of vamps which occupy the space so nobly, negates the idea that aboriginality is “synonymous with disappearance.” The bodies are there in spirit, refusing to be erased by the dominant culture.

Beading and Ceremonial Practices as Healing

Deeply matrilineal, Indigenous communities have expressed and transmitted their cultural identity and resilience through continued “gendered apprenticeships” of art making. The colonial genocide perpetrated by European empires sought to break these bonds therefore, the practice of beading speaks all the more strongly to Indigenous survivance. Coined by American scholar Vizenor in Manifest Manners (1999), the term survivance encapsulates the inherent resilience of Native narratives in their “renunciation of dominance, tragedy and victimry.” Native survivance is the active sense of presence over historical absence and the dominance of cultural simulations through the continuance of native stories.

In Belmore and Belcourt’s work, the practice of beading has been medicinal and allowed communities to mourn and ultimately to heal. In Fringe (Figure 5 for detail), the beading has literally stitched up the woman’s wound, enabling her survival. The repeated stitching of the skin and the meticulous beading remind us that the process of healing is long and painful and requires determination.

In WWOS, every aspect of the art installation, from production to viewing, is a collective act of healing. Each pair of vamps, made by volunteers responding to Belcourt’s invitation, is part of a ceremonial lodge space in which Elders guide a “cathartic ritual … for the release of trauma” (Figure 6). The communal and transcending power of beading has helped Indigenous women to “express agency.” Belcourt’s encouragement of community events like beading sessions enable matrilineal modes of transmission and connectedness, ultimately healing intergenerational trauma and “constructing strong and resistant societies” (Figure 6). Both artists use traditional techniques like beading to subvert Western conceptions of what constitute ‘authentically Indian’ art, showing how Indigenous art practices are still thriving, evolving, and innovating today.

Indigenous Visibility & Land Acknowledgement

As bold public statements of social activism that physically and mentally engage viewers, Belmore and Belcourt’s artworks use the female body as a metaphor for the exploitation and colonization of land. Acting as land acknowledgements, Fringe is an imposing billboard, part of the Resilience, The National Billboard Exhibition Project which reinserts Indigenous presence into the Montreal landscape and WWOS’s touring across Canada and the United States symbolically spreads awareness of Indigenous voices and resilience. On the city highway, Fringe’s lightbox is dramatically arresting and forces viewers to stop and reflect. Belmore reclaims photography as a weapon whilst denouncing the ongoing colonial romanticized clichés begun by American photographer Edward Curtis in the late nineteenth century. Belcourt’s WWOS is anchored in the spiritual significance of Indigenous land rights. In every installation, the vamps are laid on the floor on long rows of blood red cloth, symbolically taking up the physical space and speaking of the agonizing journey to rehabilitation and empowerment. To view the vamps in detail involves the physical act of bowing down to them requiring the viewer to spiritually connect with the land upon which they lay, reminding non-Native viewers of the historically consequential claims of terra nullius or ‘nobody’s land.’

Conclusion

There still exists in the Western contemporary psyche, colonial framings of Indigenous communities as a “vanishing race.” The Canadian genocide is the direct result of institutionalized gendered legacies but Belmore and Belcourt’s works not only acknowledge and honor MMIW, they represent the ongoing presence and resilience of survivors as sovereign entities. Ultimately, by expressing a “refusal to vanish”, they reflect the failure of the colonial project to annihilate them.

Bibliography

Allaire, Christian. “This Indigenous Peoples Day, Support Authentic Native Artists.” Vogue. Last modified October 12, 2020, https://www.vogue.com/article/indigenous-peoples-day-shopauthentic-brands.

Anderson, Stephanie G. “Stitching through Silence: Walking with Our Sisters, Honoring the Missing and Murdered Aboriginal Women in Canada.” Textile: Clothes and Culture, Vol. 14:1 (2016): 84-97. https://doi.org/10.1080/14759756.2016.1142765.

Bell, Gloria J. “Interview with Christi Belcourt, Contributing Artist and Coordinator for Walking with Our Sisters.” Interview by Gloria Bell. Aboriginal Curational Collective. 2012.

Bell, Gloria J. "Voyageur Re-presentations and Complications: Frances Anne Hopkins and the Métis Nation of Ontario." Wicazo Sa Review 28, no. 1. 2013. 100-18. doi:10.5749/wicazosareview.28.1.0100.

Bird, Elizabeth. “Savage Desires: The Gendered Construction of the American Indian in Popular Media.” In Selling the Indian: Commercializing and Appropriating American Indian Cultures, edited by Carter Jones Meyer and Diane Roger, 62-98. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2001.

Bonita, Lawrence. “Gender, Race, and the Regulation of Native Identity in Canada and the United States: An Overview.” Hypatia 18.2. Indigenous Women in the Americas (Spring 2003): 3-31.

Bratich, Jack Z., and Heidi M. Brush. 2011. “Fabricating Activism: Craft-Work, Popular Culture, Gender.” Utopian Studies 22 (2): 233-260.

Kang, Surman. “Indigenous Women and Youth In The Sex Trade: A Systematic Review Of Culturally Relevant Support Systems For Exiting The Trade.” PhD diss., University of Windsor, 2017.

Lauzon, Claudette. 2008. “What the Body Remembers: Rebecca Belmore’s Memorial to Missing Women.” In Precarious Visualities. New Perspectives on Identification in Contemporary Art and Visual Culture, edited by Olivier Asselin, Johanne Lamoureux, and Christine Ross, 155-179. Montréal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Miles, John D. “The Postindian Rhetoric of Gerald Vizenor.” College Composition and Communication Vol. 63, No. 1 (September 2011): 35-53.

Mithlo, Nancy Marie. “Introduction: Our Little Indian Woman. Beyond the Squaw/Princess.” In

“Our Indian Princess”: Subverting the Stereotype, 1-14. Sante Fe, N. M.: School for Advanced Research Press, 2009.

Native Women’s Association of Canada. “What Their Stories Tell Us: 2010 Research Findings from the Sisters In Spirit initiative.” https://www.nwac.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/2010-What-Their-Stories-Tell-Us-Research-Findings-SISInitiative.pdf.

Nawaz, Zaynab. “Maze of Injustice: The Failure to Protect Indigenous Women from Sexual Violence in the USA.” Conference paper, 135st APHA Annual Meeting and Exposition, 2007.

Otto, Elisabeth. “The Affect of Absence: Rebecca Belmore and the Aesthetico-politics of ‘unnameable affect.’” Atlantic: Critical Studies in Gender, Culture & Social Justice 38, no. 2 (2017): 92-104.

Racette, Sherry Farrell “‘This Fierce Love’: Gender, Women, and Art Making.” In Art in Our Lives: Native Women Artists in Dialogue, edited by Cynthia Chavez Lamar and Sherry Farrell Racette with Laura Evans, 27-51. Santa Fe: School for Advanced Research, 2010.

Ritter, Kathleen. “The Reclining Nude and Other Provocations.” In Rising to the Occasion, edited by Daina Augaitis and Kathleen Ritter. Canada: Vancouver Art Gallery, 2008.

Robertson, Kirsty and J. Keri Cronin. “’The Named and the Unnamed’: Gendering the Canadian Art Scene.” In Imagining Resistance: Visual Culture and Activism in Canada, edited by Kirsty Robertson and J. Keri Cronin, 115-119. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2011.

Royal Canadian Mounted Police. “Missing and Murdered Aboriginal Women: A National Operational Overview.” Last modified May 27, 2014. https://www.rcmpgrc.gc.ca/wam/media/460/original/0cbd8968a049aa0b44d343e76b4a9478.pdf.

Skelly, Julia. “Alternative Paths: Mapping Addiction in Contemporary Art by Landon Mackenzie, Rebecca Belmore, Manasie Akpaliapik, and Ron Noganosh.” Journal of Canadian Studies, vol. 49, no. 2 (Spring 2015): 268-95.

Wakeham, Pauline. “Introduction: Tracking the Taxidermic.” In Taxidermic Signs: Reconstructing Aboriginality, 1-74. Minneapolis; London: University of Minnesota Press, 2008. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctttvc3k.

Walker, Ellyn. “Resistance as Resilience in the Work of Rebecca Belmore.” In Desire Change: Contemporary Feminist Art in Canada, edited by Heather Davis, 135-148. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2017.

Appendix

[1] Ellyn Walker, “Resistance as Resilience in the Work of Rebecca Belmore,” in Mentoring Artists for Women’s Art, eds. Heather Davis (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2017), 137.

[2] Zaynab Nawaz, “Maze of Injustice: The Failure to Protect Indigenous Women from Sexual Violence in the USA,” (Conference paper, 135th APHA Annual Meeting and Exposition 2007); Nancy Marie Mithlo, “Introduction: Our Little Indian Woman. Beyond the Squaw/Princess,” in “Our Indian Princess”: Subverting the Stereotype (Sante Fe, N. M.: School for Advanced Research Press, 2009), 12.

[3] Sherry Farrell Racette, “‘This Fierce Love’: Gender, Women, and Art Making,” in Art in Our Lives: Native Women Artists in Dialogue, ed. Cynthia Chavez Lamar and Sherry Farrell Racette with Laura Evans (Santa Fe: School for Advanced Research, 2010), 45-46.

[4] Elizabeth Bird, “Savage Desires: The Gendered Construction of the American Indian in Popular Media,” in Selling the Indian: Commercializing and Appropriating American Indian Cultures, ed. by Carter Jones Meyer and Diane Roger (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2001), 90.

[5] Pauline Wakeham, “Introduction: Tracking the Taxidermic,” in Taxidermic Signs: Reconstructing Aboriginality, (Minneapolis; London: University of Minnesota Press, 2008), 37.

[6] Kathleen Ritter, “The Reclining Nude and Other Provocations,” in Rising to the Occasion, (Canada: Vancouver Art Gallery, 2008), 65.

[7] Bell, Gloria J, "Voyageur Representations and Complications: Frances Anne Hopkins and the Métis Nation of Ontario," Wicazo Sa Review 28, no. 1. (2013). 108.

[8] Surman Kang, “Indigenous Women and Youth In The Sex Trade: A Systematic Review Of Culturally Relevant Support Systems For Exiting The Trade” (PhD diss., University of Windsor, 2017), 5.

[9] Bird, “Savage Desires: The Gendered Construction of the American Indian in Popular Media,” 79. 10 Racette, “This Fierce Love’: Gender, Women, and Art Making,” 35.

[10] Stephanie G Anderson, “Stitching through Silence: Walking with Our Sisters, Honoring the Missing and Murdered Aboriginal Women in Canada,” Textile: Clothes and Culture, Vol. 14:1 (2016): 87-88.

[11] Wakeham, “Introduction: Tracking the Taxidermic,” 13.

[12] Racette, “This Fierce Love: Gender, Women, and Art Making,” 31; Anderson, “Stitching through Silence: Walking with Our Sisters, Honoring the Missing and Murdered Aboriginal Women in Canada,” 92.

[13] John D. Miles, “The Postindian Rhetoric of Gerald Vizenor,” College Composition and Communication Vol. 63, No. 1 (September 2011), 40; Racette, “This Fierce Love’: Gender, Women, and Art Making,” 34.

[14] Anderson, “Stitching through Silence,” 86.

[15] Racette, “This Fierce Love: Gender, Women and Art Making,” 46.

[16] Anderson, “Stitching through Silence,” 91.

[17] Anderson, “Stitching through Silence,” 88; Racette, “This Fierce Love: Gender, Women and Art Making,” 34.

[18] Christian Allaire, “This Indigenous Peoples Day, Support Authentic Native Artists” Vogue, last modified October 12, 2020, https://www.vogue.com/article/indigenous-peoples-day-shopauthentic-brands.

[19] Claire Raymond, “Rebecca Belmore : The Photograph’s Wound,” last modified May 4, 2014, https://www.claireraymond.org/icons-of-estrangement/.

[20] Claudette Lauzon, “What the Body Remembers: Rebecca Belmore’s Memorial to Missing Women,” in Precarious Visualities (McGill-Queen’s University Press), 159.