These Monuments Are Already Spoken For

by Jacob Anthony

Otherworldly concrete monuments, abandoned in the hills of Bosnia and Croatia. They’re futuristic yet ancient, alien yet earthly, and they could be relics of a lost Balkan civilization as much as they could be monoliths of the future à la 2001 Space Odyssey. With The Unknown being such a hot commodity in this age of all-knowing, the images naturally got attention. A drawback of expedited image-sharing, though, is that the monuments were just as expeditiously stripped of context. So, what began as a memorial to the victims of the Battle of Sutjeska in 1943 is now circulated far and wide as the enigmatic Spomenik #16. Built to embody victory, for a liberated Yugoslavia and its people, it’s now an icon of the opposite. Of a ‘lost’ future. Such is the case for many of the World War II monuments of former Yugoslavia. In 2018, for example, an Australian sunglasses company used Spomenik #9 as a backdrop for their spring collection. What they assumed was an evocative megalith was actually a memorial to the hundreds of thousands killed in the Jasenovac death camps. Upset followed.

Spomenik is the Serbo-Croatian word for “monument.” The current spomenik-revival has anglicized the term to relate the unrelated sites as a plural, as the spomeniks. They’re sometimes accompanied by numbers, and less often locations, but seldom are they granted proper names. 2010 saw Belgian photographer Jan Kempenaers capture this exoticism perfectly albeit unintentionally in his book, “Spomenik.” The appropriation of these cultural landmarks has received some, but not much opposition, as Yugoslavia’s prolonged and still-raw dissolution throughout the 1990s has left very few who care to defend the bygone state’s fossils. Thus, many of the 40,000 monumental objects honoring Yugoslav sacrifice in WWII have been lost through neglect or intentional demolition.

Altogether, the story of the “spomeniks” is a fraught one. They were conceived to memorialize victims of political violence, and many became casualties themselves less than 20 years later in the Yugoslav wars. The surviving monuments have in turn been snatched up by the internet’s connoisseurs of ruin porn, and one can only imagine what is still to come for these sculptures. What were once the pinnacles of Yugoslav art have now become nameless and mute artefacts for the masses, and yet another cautionary tale of cultural possession.

I. MONUMENTS

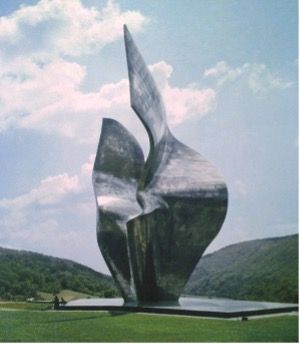

Vojin Stojić & Gradimir Medaković, The Battle of Sutjeska Memorial Monument Complex in the Valley of Heroes, 1971. Tjentište, Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The “spomeniks,” first and foremost, were created in honor of Yugoslav anti-fascism, but to understand what led to the monuments, one must understand what led to Yugoslavia. Notions of a single, unified Slavic state preceded Yugoslavia itself by several centuries, beginning in the late 1600s, although it would take a further 200 years for the idea to gain worthwhile traction. In 1918, after the dust of World War I had settled, the idea was brought to fruition as the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. In 1929, the territory was rebranded under the more familiar ‘Yugoslavia’. King Aleksander concomitantly eliminated all political parties and began his reign as dictator. In the decade that followed, Aleksander was assassinated, his cousin, Prince Pavle, took power, submitted to fascist pressure, got deposed by a coup, and left the country embroiled in a fair bit of chaos.

On April 6th, 1941, less than two weeks after Prince Pavle’s capitulation, Hitler invaded the capital of Belgrade. Thus began Yugoslavia’s involvement in World War II. Several resistance movements emerged, including one backed by the communist party, and another partisan resistance led by Josip Broz Tito. Yugoslavia and Greece were the only countries during the war to have such resistances. The next four years saw these uprisings merge and morph from anti-fascist liberation to socialist revolution, a goal that was finally realized in 1945 with Yugoslavia’s emancipation as a communist state. Josip Broz Tito was recognized as a national hero, and Yugoslavia subsequently elected him president.

As will be explored through the monuments it precipitated, the National Liberation Struggle cast a long shadow on Yugoslavia, and was regarded by most as the event in the young nation’s history. Between 1941 and 1945, 1.7 million Yugoslavs were lost through death or displacement. Within Europe, this figure was only surpassed by Poland.

As a reborn communist state, Yugoslavia looked to the system’s best-known implementation, the USSR, as a model for its burgeoning socio-economic policies. But, in the years following World War II, the two commonwealths experienced an ideological split. At the time, the USSR’s satellite states met the northeast border of Yugoslavia, and what began as a matter of geopolitics in these border regions snowballed into an unceremonious diplomatic divorce. Tito became the anti-Stalin, focusing his efforts on decentralizing the state and cultivating a new “market socialism.” Yet, this separation is what catalyzed the spomeniks’ design.

During and after World War II, the school of Social Realism was experiencing a heyday in Russian monumental art. For nearly a century, artists had been using the style to venerate the working class, and ergo Social Realism found a fitting application in promoting communism. Men, women, and children are shown armed with hammer and sickle, together fighting their way to a glorious Marxist future. Such was the uniting imagery of Soviet art post-WWII, and its wake can still be seen throughout Russia and its former assets. Before the rift, Yugoslavia also made use of Social Realism, manifestations of which are visible in its few surviving examples of pre-1950 monumental art.

Even so, Yugoslavia’s newfound independence brought on a need for an equally independent identity. Heavy-handed USSR iconography was discarded in favor of more fluid forms, devoid of symbols and usually lacking in human likenesses altogether. It was in part an effort to depart from the Soviet way, and also an attempt at reconciliation. Yugoslavia encompassed a vast array of ethnic and religious groups with conflicted histories. Through amorphous, optimistic abstractions that began at the ground and blossomed outwards towards the sky, the hope was that a message of cooperative growth and emergence could be communicated. Not one that throttles the viewer as in the Soviet style, but one felt in the abstract. Thus, the aim of the sculptures was not to glorify the Yugoslavian state, but rather to unify the sacrifices that created it.

Yevgeny Vuchetich, The Motherland Calls, 1967. Volgograd, Russia.

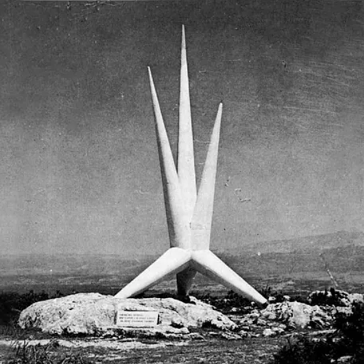

Vojin Stojić & Gradimir Medaković, Monument to the Fallen Soldiers of the Kosmaj Detachment, 1971. Kosmaj Mountain, Serbia.

But union was not the only message these monuments aimed to impart. In the words of Sandina Begić and Boriša Mraović,“Yugoslavia…was an ultimate expression of social constructivism…a revolutionary system almost openly declaring its contingent and constructed nature. No wonder then the size and grandeur of the socialist monuments! The system, revealing itself as openly ‘under construction,’…had to ground its symbolic regime literally into the ground, and to make it, if not indestructible, then at least immovable.” In other words, the young Yugoslavia made no attempt to root itself in mythologies. It admitted its novelty and made that the core pillar of its design philosophy. The resulting sculpture was sleek, kinetic, and startling, all the makings of a futuristic state.

As well as futurism, the style was shaped by a need for ambiguity. With the Yugoslav population’s many impassioned differences, an attitude arose after WWII that forbade any public discussion of the war’s atrocities, a phenomenon Begić and Mraović call the “politics of leaving things unsaid.” Hence, the monuments that were to commemorate this unspoken past needed to be equivocal, decorous, and, in essence, mute. Any interpretation found therein was highly personal, and not instructed as in social realism. This is why the monuments symbolize a hopeful future, for any reference to the past’s agony could beget strife.

II. ICONOCLASM

Vuko Bombardelli, Monument to the 1st Split Partisan Detachment, 1961 & 2007. Košute, Croatia.

The “politics of leaving things unsaid,” although effective in the short term, would become Yugoslavia’s undoing, for what was unspoken in public found a more aggrieved voice behind closed doors. This segregation of discourse plus other internal contradictions brought the country to a breaking point in 1991 with the onset of the Yugoslav wars. Yugoslavia’s dissolution was, in theory, supposed to run smoothly, with defined outcomes and designated agents to execute them. As we now know, this was not the case, and the decade that followed would prove disastrous for the monuments and the peace they stood for.

Broadly defined, iconoclasm is the destruction of art for religious or political purposes. For as long as art has held collective value, humans have used it as both a weapon and a mode of protest. In a recent instance, anti-racism protesters toppled Confederate and slave-owner statues during the George Floyd protests of 2020. Similar sentiments abounded in the years during and after the Yugoslav wars, where the nationalistically-biased began to view the monuments as symbols of “the old system.” Accordingly, many were demolished. As seen above, the memorial at Košute was one such victim. On August 21st or 22nd (the exact date is unknown) of 1992, the monument was laden with explosives and razed to the ground. Today, the plaque that once read:

VJESNICIMA SLOBODE

KOJI DADOŠE I MLADOST I ŽIVOT

ZA ŽIVOT DOSTOJAN ČOVJEKA

“To those who brought us freedom,

who gave their youth and their lives,

so that we may live and value our own lives.”

Has been so eloquently replaced by graffiti like:

BOLJE RUKA NA PIĆKA

NEGO NA STROJA

“Better the hand on the pussy

Than on the machine gun.”

A 2017 investigation by Jelena Buljan found that all police reports relating to the demolition were at some point also destroyed. No efforts have been made to reinstall the sculpture, and it currently lies in broken chunks on a hilltop above the town. Though many have characterized the Yugoslav iconoclasm as a crime against art and state, it begs the questions: who gets to decide the fate of these monuments, if not the people they were built for?

Vojin Bakić, Monument to the Victory of the Slavonian People, 1968 & 1992. Kamenska, Croatia.

It isn’t known how many of the monuments survived the wars, and no comprehensive surveys have yet been undertaken on their condition. But, with mystery comes fascination, and the surviving memorials were photographed and spread among the architecture savants of the Internet. The “Spomenik – #” labels only added to the enigma, and thanks to missing context, fabricated histories emerged.

One of the most prevailing of these myths declares that the “spomeniks” were commissioned by Josip Broz Tito himself. To those familiar with Yugoslavian history, this isn't a difficult thing to believe. Tito, for better or worse, was a nationalist and the greatest proponent of the Yugoslavian image. Memorializing the sacrifice that earned him his position would not be out of question. With that said, the majority of the memorials were commissioned locally and funded through public donations, not by an autocrat or the government’s purse. Tito ran Yugoslavia as a decentralized entity, allocating much of the decision-making and funding responsibilities to its six republics. In later years, the monuments’ commissions were managed by SUBNOR, a national veteran group, but they were still selected through design competitions and by local juries. Incidentally, those design competitions are now believed to have dictated the trajectory of Yugoslav modernism.

The most concerning part of the monument’s revival, though, is the erasure of the anti-fascist struggle they were built for. This was a fate the “spomeniks” were particularly susceptible to, seeing as most lack visual reference to the past that caused them. On top of that, many (like the Podgarić monument seen in the first image) lack descriptive plaques altogether, as either funding or motivation ran dry before their installation. The “spomenik” images in circulation are thus construed as ancient, with no one left to speak for them. But of course, the enigma is the appeal. The problem with this, aside from the obvious pitfalls of cultural appropriation, is how it affects Yugoslavia’s successor states. In Croatia, for example, the current right-wing administration has shown overt nostalgia for the fascist Ustaše group of the 1930s and 40s. Suppressing the nation’s anti-fascist past is in their best interests, and the internet’s contextual pillaging of the monuments only encourages it.

In this sense, the monuments that survived the Yugoslav wars’ iconoclasm are being subjected to a new threat — representational violence. Art historians understand representation violence as a type of “symbolic violence,” or violence without physical attack, that harms individuals or groups through false characterization. The term is most often attributed to racist art, wherein the artist’s racial prejudice corrupts the image of the nonwhite subject. The term can also be applied to the monuments; the Internet has renamed them, stripped them of context, and hence construed them as something they are not. Though the harm done thereof was through exoticization and not malice, it still has serious implications for the integrity of Yugoslavia’s heritage. Moreover, the generation of Yugoslavs that poured the concrete for these memorials is still alive. The “spomeniks” are still their monuments, and the sculptures still constitute their loss.

III. RUBBLE

Hubert Robert, The Colosseum in Rome, 1790, Oil on canvas. Madrid, Museo del Prado.

Humans have admired the grandeur of ruins for as long as there have been ruins to admire. Upon discovering the crumbling remains of Rome, northern European Rococo artists rendered this fascination in paint, and the resulting genre was accordingly termed capriccio, or “fantasy.” The derelict classical architecture shown was sometimes real, sometimes imagined, and sometimes both (see Hubert Robert’s other great work of the 1790s, View of the Grande Galerie of the Louvre in Ruins). As art progressed into the wasteland-obsessed Romanticism movement, the mystique of ruins became all the more sought-after. This time, the rubble itself was overshadowed by the powers of nature that made it so. Nonetheless, fantastical fragments of architecture appear throughout. Today, romanticism and rubble are key commodities of the internet business, and social media’s tendency to reduce images to their very contextless essence only deepens the allure, albeit at the cost of cultural histories. What the internet sought in the spomeniks was likely the same thing Rococo artists sought in the ruins of Rome: monuments without a voice, that one could marvel at without inconvenient narratives interrupting the view.

Vladimir Dobrović & Alija Kučukalić, Vraca Memorial Park, 1981. Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina.

But what of those that live among the monuments? In 1999, a reporter for the Bosnian periodical BH DANI visited the ruined Vraca memorial in Sarajevo. When he asked a boy playing nearby if the memorial belonged to ‘us’ (Bosnia), the boy replied, “No, it is Tito’s.” It is fascinating, then, that through a lived experience of the Yugoslav conflict, he would come to the same conclusion as uninformed Yugoslav romanticists. Though one can hardly expect a single Bosnian boy to speak for seven nations, his words beg a new question: whose monuments are these, if no one wants them at all?

But the “spomeniks” aren’t the ruins of Shelley’s Ozymandias, monuments to hubris dismantled by time, nor are they just weird heirlooms of modernism. They still stand atop mountains, in cities, and along country roads, each with scores of individuals able to speak to their purpose. Some, like the Sutjeska monument seen in the first image, are now receiving their first cleaning in decades, restoring drab concrete to the ivory white of better days. There will be ceremonies for the anniversaries, and public interest will ebb and flow, and maybe, centuries from now, the monuments will crumble and the memories with them. But these monuments aren’t about Yugoslavia. Memorials are built for the people that died for the state, not the state that died for the people.

WORKS CITED

Armakolas, Ioannis. 2015. “Imagining Community in Bosnia: Constructing and Reconstructing the Slana Banja Memorial Complex in Tuzlapp.” In War and Cultural Heritage, 225-250. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Begić, Sandina, and Boriša Mraović. 2014. “Forsaken Monuments and Social Change: The Function of Socialist Monuments in the Post- Yugoslav Space.” In Symbols that Bind, Symbols that Divide: The Semiotics of Peace and Conflict, 13-37. Berlin: Springer.

Burjan, Jelena. 2017. “Srušeni spomenik pripadnicima Prvog splitskog partizanskog odreda u Košutama kod Trilja.” SREDNJA STRUKOVNA ŠKOLA BANA JOSIPA JELAČIĆA U SINJU, (September).

Dizdarević, Leila, and Alma Hudović. 2013. “The Lost Ideology: Socialist Monuments in Bosnia.” In 1st International Conference on Architecture & Urban Design: Proceedings 19-21 April 2012, 455-464. Tirana, Albania: EPOKA University.

Hatherly, Owen. 2016. “Concrete clickbait: next time you share a spomenik photo, think about what it means.” The Calvert Journal. https://www.calvertjournal.com/articles/show/7269/spomenik-yugoslav-monument-owen-hatherley.

Janjevic, Darko. 2018. “Australian Valley Eyewear firm shoots ad at Jasenovac death camp.” Deutsche Welle, March 7, 2018. https://p.dw.com/p/30m40.

Jezernik, Božidar. 2011. “No Monuments, No History, No Past: Monuments and Memory.” In After Yugoslavia: Identities and Politics within the Successor States, 182-191. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Niebyl, Donald. 2016. “Spomenik Database.” www.spomenikdatabase.org.

“Planning, Equipment And Evaluation Of Monuments From World War II in Yugoslavia.” 2019. Arhitektura i urbanizam 49, no. 1 (December): 60-69.

Stevanovic, Nina. 2018. Architectural Heritage of Yugoslav-Socialist Character: Ideology, Memory and Identity. Barcelona: Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya.

IMAGES USED

1. Kempenaers, Jan. Spomenik #1 (Podgarić), 2006. 2007. Jan Kempenaers. Accessed February 17, 2021. www.jankempenaers.info/works/1/.

2. Niebyl, Donald. Battle of Sutjeska Memorial Monument Complex. Spomenik Database. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://www.spomenikdatabase.org/tjentiste.

3. Miklós, Vincze. Mamayev Kurgan. 2013. These Mega-Sculptures Are the Biggest in the World. Accessed February 17, 2021. io9.gizmodo.com/these-mega-sculptures-are-the-biggest-in-the-world-1468095522.

4. Pyzik, Agata. Kosmaj Monument. 2013. A Thousand and One Look at Yugoslavian Architecture. Accessed February 17, 2021. http://nuitssansnuit.blogspot.com/2013/01/a-thousand-and-one-look-at-yugoslavian.html.

5. Niebyl, Donald. Košute Spomenik (1960s). Spomenik Database. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://www.spomenikdatabase.org/kosute

6. Kempenaers, Jan. Spomenik #12 (Košute), 2007. 2007. Jan Kempenaers. Accessed February 17, 2021. www.jankempenaers.info/works/1/10.

7. Niebyl, Donald. Monument to the Victory of the Slavonian People. Spomenik Database. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://www.spomenikdatabase.org/kamenska.

8. Miloš, Vatroslav. Spomenik pobjedi naroda Slavonije Vojina Bakića kojeg su 1992. 2015. Red, rat i disciplina. Accessed February 17, 2021. www.kulturpunkt.hr/content/red-rat-i-disciplina?quicktabs_rss=0&quicktabs_izdvojeno_i_komentari=0&quicktabs_abeceda_i_kinemaskop=1

9. Hubert Robert, The Colosseum in Rome, 1780-1790, oil on canvas, 240 x 225 cm., Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid. Accessed February 17, 2021. www.museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/art-work/the-colosseum-in-rome/217c3bc5-f89a-424c-b750-f8416f6ebcce

10. User MOs810. Vraca Park. 2010. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vraca_Park.JPG