Indigenous Matrilineality: Resisting Annihilation Through Arts And Spirituality

Charlotte Pierrel is a third-year student in Art History and Psychology at McGill University.

Content Warning: This article contains mentions of colonial genocide and intergenerational trauma that might be disturbing or triggering.

Despite the historical and still ongoing regulation of Indigenous identities, contemporary Indigenous artists have gradually found their voice since the 1970s, using art production to celebrate their cultures with fierce pride. Specifically, Indigenous women artists from Northern communities of Turtle Island, Canadian Métis visual artist Amy Malbeuf and Inuk artist Shuvinai Ashoona, are part of a blossoming generation of Indigenous artists wrestling with the devastating legacies of European settler-colonialism and subverting Western conceptions of Indigeneity through the decolonial power of the arts. Analyzing their respective artworks Métis Explosion Mukluks(2012, Figure 1) and The World in Her Eyes (2011, Figure 2), they represent a significant culmination in the struggle against colonial repression and most especially the ongoing marginalization of Indigenous women.

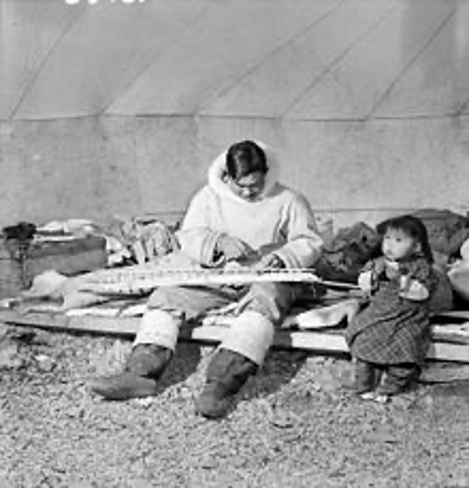

Despite their distinctively formal differences, both artworks also share roots in the importance of the natural world, the spirituality inherent in their culture and the long tradition of craft skills and storytelling. Historically, Indigenous women have constituted the backbone of Indigenous art and culture which was sustained by making art and telling stories collectively. Deeply matrilineal, Indigenous women of the Northwest have played an important role in cultural endurance, and these artworks are reclamations seeking to rebuild cultural ties through art making and storytelling. Employing formalist and post-colonial methods, we will argue that both artworks reclaim Indigenous materiality, thereby constituting decolonial symbols of Indigenous resilience which respond to historical and contemporary manifestations of Western oppression through the making of art.

The formal choices of each artwork have enabled both Malbeuf and Ashoona to respectively reclaim their Métis and Inuit cultural patrimony in distinct ways. Whereas Métis Explosion Mukluks showcases Métis’ pride in its material culture, Ashoona’s The World In Her Eyesmanifests the importance of storytelling in Inuit culture, revealing how material culture and spirituality have contributed to Indigenous resilience. Métis Explosion Mukluks is a three dimensional, intricately handmade pair of Métis traditional mukluks historically produced by Northern Indigenous communities and that showcase a diverse range of material and techniques. Testament to the cultural fusion of Anishinaabe and European cultures which constitute Métis identity, the moccasins unite European floral designs and Anishinaabe hide tanning and embroidery techniques. This is shown through the use of natural materials like moose hide, coyote fur and pigskin prepared by Indigenous communities, and through the beading and rainbow ric rac ribbon introduced by colonial European settlers (Figure 3 for detail). The artist’s conscious choice of materials and technique reveal her community’s uniquely rich material culture, a distinctive artistic style that eventually led to the name ‘Flower Beadwork People.’ Its rich texture enhances proudly and loudly proclaim Métis culture and its overlapping materials convey an endless sense of continuity. This lack of boundaries symbolizes the continuity of Métis practices to this day. Almost an entirely faithful reproduction of traditional mukluks, the artist Malbeuf seems to be saying that simply to reaffirm her cultural heritage through its materiality is a sufficient artistic statement. As Native Studies scholar and artist Racette argues, “clothing has been instrumental in the active construction of Métis group identity.” Believed to unite the wearer with the Earth and the infinite world which has been created by the Creator, mukluks have been used for multiple purposes from arctic footwear to symbolic gifts of rites of passage. Mediators between the physical and spiritual world, Malbeuf’s every material enact the spirit of its animal, representing the deeply holistic relationship between humans, animals and the land, and enabling the wearer to pay respect to the Creator. Ultimately, the very material nature of the mukluk in itself emanates spirituality.

On the other hand, The World In Her Eyes is a post-colonial symbol of Indigenous resilience reflecting the powerful role of Inuit spirituality in Indigenous survivance. Coined in 1999 by Gerald Vizenor, the term survivance is the material and symbolic “active sense of presence” and “continuance of native stories” that attempt to subvert “dominance, tragedy and victimry.” Purely visual, this two-dimensional drawing depicts an Artic scene of mythology filled with hybrid creatures in a detailed and naturalistic style, its iconography evocative of Inuit old legends. As Inuit director Kunuk explains, because Inuits were excluded from the school system storytelling constituted “Inuktitut way of teaching” which he immortalized in his 2001 film, based on an old Inuit legend. Similarly, Ashoona depicts a narrative mythological story, affirming story telling as a vital part of her culture. Emphasizing interconnectedness, this is reflected in the endless hybridity of animals. The blurred boundaries between material/immaterial, reality/spirituality and past/present show how kinship networks go beyond human experience. An anthropomorphic figure stares out at the viewer from a swirling mesh of snake like forms and rainbow rivers of tentacles. The upper part of the figure’s head is made up of a pale-yellow arctic bear, a walrus and a bird’s head whose beak emerges from the figures ear and points to the edge of his left eye. Behind the figure’s head to the right, the earth’s globe, in gorgeous, marbled blues and greens is held in place by the claws of the arctic bear. The repeated motif of the Earth, echoed in the watery eyes of the figure and also revealed, duplicated in miniature within the cut ends of the snake and the ‘octopus sash’ is symbolic in uniting life and land. Although Ashoona has chosen a decidedly non-Inuit medium for her work, the subtle and precise way she uses the pencil to create an effect of etching a hard surface reference Alaskan ivory carving and the incised ornaments and tools crafted by Inuit communities.

The mere existence of these works in the contemporary world challenge colonialism which sought to eradicate Indigenous culture and subvert its myth of Indigenous extinction. According to Toronto-based writer and critic Deborah Root, they have been located in an ‘ethnographic present’ by the West to conceive them as extinct and anonymous. According to Pauline Wakeham, they “inscribe forms of ideological statis that (froze) native others in immobile poses of pastness.” Above the central band of coyote fur of the mukluks, a beaded flag proudly displays the Métis infinity symbol, echoed in the vamp. First used by resistance fighters in 1816, the infinity symbol affirms their survival and acknowledges their infinite histories. Showing Métis persistence and strive towards self-determination, the purple fringes and lacing made from pigskin are reminiscent of the whirl of fringes in a traditional potlatch dance, an important cultural practice which was forbidden under the Potlach Ban (1885-1951). Although this practice went underground for many years, First Nations still practice it today. According to Métis artist and writer David Garneau, to identify as a Métis artist by definition is to resist assimilation. Intentionally using beadwork as a tool to assert her cultural identity as a Métis artist and woman, her work is a testament to the wealth of intrinsically Métis knowledge which remains and has been successfully passed on. As Racette argues, it is vital for Métis communities to reclaim historical Métis clothing and material culture which has been historically misidentified and mislabeled in colonial archives. Considered ‘half-breeds’, Métis communities have historically struggled to be recognized as individuals because of the ‘in-betweenness of Métis identity.’ One could also read the work in parallel to Christi Belcourt’s Walking With Our Sisters commemorative installation in that it offers an optimistic view of Indigenous women’s future. In addition, the very title The World in Her Eyes indexes the artist’s desire to revisit Indigenous histories and assert her own vision of the world which has historically been dominated by Western practices of erasing and renaming, giving agency to not only her female voices but those of her community as well.

Contemporary Indigenous artists also challenge the longstanding Western desire for collecting ‘traditional’ pre-European contact art. The artworks break down Western artistic hierarchies and conceptions of what constitutes ‘authentic’ art. Whereas Malbeuf’s mukluks are rather subtle in their subversion, Ashoona’s drawing is far more radical in its approach. Indigenous artistic expression has been historically regulated and expected to fit Western understandings– Indigenous children in residential schools were forced to create generic ‘Indian art’ and much of its artistic production responded to Southern expectations. Métis communities suffered from these conceptualizations - Europeans were unwilling to buy beadwork from a Métis, who were considered to be unauthentically ‘Indian’ and so their work would be credited to the Cree or Ojibwe. Compared to traditional Native moccasins, Malbeuf’s interpretation of the footwear breaks away from her community’s ancestry – far more colorful, they are much more adorned and gorged with decorative patterns. This creation of a new aesthetic reflects a new form of materialism. In contrast, The World In Her Eyes departs more drastically from traditional media, subverting what Inuit art should traditionally be and look like. According to Root, “the non-Inuit viewer is confronted with his or her assumptions about life in the North.” Contemporary films like Atanarjuat also, as Louis Bessire explains, “undermine the perpetuation of primitivism.” Igloliorte’s scholarly work unsettles the legacies of settler-colonialism in an attempt to center Indigenous history and art within the broader Canon. Indeed, the Canadian Handicrafts Guild in 1930s sought to push for the recognition of Inuit crafts (Figure 4). The pencil was only introduced to Inuit communities in the 1950s when artist James Houston established its first printshop, now renowned Kinngait Studios, for local Inuit artists to experiment traditional art forms with contemporary techniques in Cape Dorset (Figure 5). Ashoona weaves Inuit elements into the drawing which then becomes a springboard for an imaginative and individual vision of her community. Highly influenced by pop culture, her inspirations include horror, comic books and TV. Additionally, the colorful stripe motif which takes the form of an octopus’s tentacle is reminiscent of traditional finger woven sashes, a reminder to non-Indigenous viewers that these techniques are still practiced today. Possibly the most widely recognized symbol of Métis culture, “The Order of the Sash” is indeed given to members of the Métis community who have made a significant contribution to their people - more than just a decorative piece of clothing, it plays an important role in the understanding of Métis identity.

Despite the attempted cultural genocide of Indigenous communities, Métis Explosion Mukluksand The World in Her Eyes are testaments to how art production and spirituality has enabled Métis and Inuit cultures to survive. Inviting the viewer to revise history from an Indigenous point of view, they offer a cultural critique that challenge the place of Indigenous people in the art world and in contemporary society. Their mere existence are testimony to the resilience of Indigenous women have shown, and thus their role in healing intergenerational trauma through arts.

Bibliography

Anderson, Stephanie A, “Stitching through Silence: Walking With Our Sisters, Honouring the Missing and Murdered Aboriginal Women in Canada”, (TEXTILE, 2016): 89.

Bell, Gloria. “Oscillating identities: Re-representations of Métis in the Great Lakes Aera in the Nineteenth Century” in Métis in Canada: History, Identity, Law and Politics (The University of Alberta Press: 2013).

Bessire, Lucas. “Talking Back to Primitivism: Divided Audiences, Collective Desires” in American Anthropologist (Language Politics and Practices, December 2003): 835.

Chun, Kimberly and Kunuk, Zacharias. “Storytelling in the Arctic Circle: An Interview with Zacharias Kunuk.” Cinéaste 28.1 (Winter 2002): 21-23.

Garneau, David, “Contemporary Métis Art: Prophetic Obligation and the Individual Talent” in Close Encounters: The Next 500 Years. Ed. Sherry Farrell Racette. (Winnipeg: Plugin Editions, 2011): 110.

Igloliorte, Heather. “The Inuit of Our Imagination” in Inuit Modern: The Samuel and Esther Sarick Collection. (Ed. Gerald McMaster. Toronto: Art Gallery of Ontario; Vancouver: Douglas &McIntyre, 2010): 41-47.

Kunuk, Zacharias. Atanarjuat The Fast Runner (National Film Board of Canada: 2000).

Payne, Carol and Thomas, Jeffrey. “Aboriginal Interventions Into the Photographic Archive: A Dialogue Between Carol Payne and Jeffrey Thomas.” Visual Resources: An International Journal of Documentation 18:2 (2002): 109-125.

Racette, Sherry Farrell, “Beads, Silk and Quills: The Clothing and Decorative Arts of the Metis” in Métis Legacy (2001): 185.

Root, Deborah. “Inuit Art and the Limits of Authenticity,” in Inuit Art Quarterly 23.2 (Summer 2008): 10.

Wakeham, Pauline. “Celluloid Salvage: Edward S. Curtis’s Experiments with Photography and Film” in Taxidermic Signs: Reconstructing Aboriginality(Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008): 93.